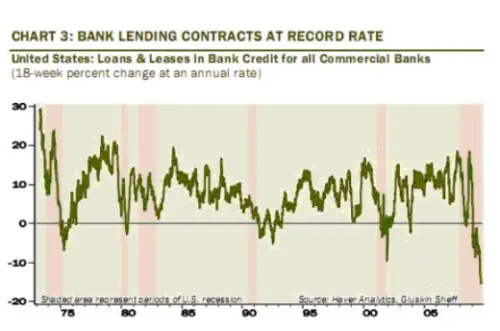

How do you define inflation? In some ways it’s a slippery thing, like trying to nail Jell-O to a tree. One common definition amounts to “a general and sustained rise in the price of goods and services.” Another is “a persistent decline in the purchasing power of money.”

Others argue that inflation is directly tied to the money supply. That is to say, they believe a substantial rise in the money supply is the same thing as inflation. (This is one small step removed from Milton Friedman’s old assertion: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”)

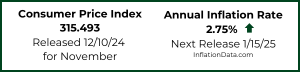

Why is the debate important? Because of the infamous chart you see below (courtesy of hedge fund QB Partners and the St. Louis Fed) and all the investing implications that stem from it.

Chances are high you’ve seen that chart before. It’s been referenced countless times (including more than once in these pages). It’s been cited so many times, in fact, that your editor is admittedly getting a bit tired of it.

Some investors say the Fed’s unprecedented expansion of the monetary base — that vertical rocket shot pictured in the chart — acts as proof in itself that inflation is here. These investors directly define inflation as a change in the money supply. They make a straight connection between pumping more dollars into the system (expanding the money supply) and inflation’s immediate presence.

Mind the Lag

With all due respect to the late great Milton Friedman, your humble editor rejects this notion. Inflation is NOT the same thing as a change in the money supply. A dramatic expansion of the U.S. monetary base does NOT automatically count as inflation. It does NOT automatically mean that inflation is here.

Let’s see if we can sort this out without making things too complicated…

To begin, one should remember that monetary policy acts with a lag. When the Federal Reserve changes something, you don’t always see the result right away… and the result isn’t always the desired one. Think of a very old water heater in a very old house. When you turn the faucet to “hot,” you won’t get hot water right away. It might take 30 seconds, or it might take three minutes. If the heater and the pipes are in a poor enough state of repair, you might not get any hot water at all.

It is true that dramatic increases in the money supply eventually lead to inflation (in the vast majority of cases). But the key word there is “eventually.” Sometimes it can take a while. The size of the lag depends on general conditions… and a very important concept known as “monetary velocity.”

Don’t Forget Velocity

In November of 2008, we ran a piece titled “The Importance of Monetary Velocity.” If you want to get your head around why velocity is so important, it’s worth a read. To quickly recap here, inflation and deflation are not purely functions of how much money is the system. They are functions of how fast that money is moving through the system.

When banks are lending, businesses are borrowing, and consumers are spending, money changes hands quickly. It zips around like molecules in a heated gas chamber. Under these conditions, we can say that monetary velocity is high.

Conversely, when banks are turtled up, businesses are hunkered down, and consumers are saving or paying down debt, money does not change hands quickly. It moves slowly and lethargically, like sluggish molecules in a cooled gas chamber. If the economy grinds to a near halt – as it did in late 2008 – money stops changing hands completely, like gas particles cooled to a liquid state (and puddled on the floor).

So here is the thing. You don’t get inflation purely from an increase in the money supply. You also need sufficient monetary velocity to spur “a general and persistent increase in the price of goods and services.” If you don’t get that velocity –- if the money doesn’t move through the system –- there is no reason for prices to rise.

Here is another slightly weird example to illustrate the point. Say, for some oddball reason, that the Federal Reserve decided to create a trillion dollars out of thin air and give it to Bill Gates. (No special reason it’s Bill Gates, just picking a name here.) Let us further say, for the sake of example, that Bill Gates has agreed to keep this trillion-dollar windfall in a non-interest bearing checking account, i.e. to just let it sit there.

This would be a de facto expansion of the money supply, yes? A trillion new dollars now exist that didn’t exist before. But these dollars aren’t circulating through the system in any way, so how can they have an impact?

The point is, it’s not just about how many dollars are being printed. It’s about where those dollars go and how fast they are moving through the system.

Debt Is Like a Sponge

Something else to consider: When it comes to changes in the money supply, debt acts like a sponge.

That is to say, if excess monetary reserves are like water threatening to “flood” the system, then large quantities of debt are like giant sponges soaking up that water. Or if money is like matter, debt is like anti-matter. It is negative money… money already spent.

Take the average U.S. consumer for example. When all the different forms of debt are added up – mortgage debt, credit card debt, vehicle financing and so on – the typical consumer is very deep in debt right now. By some estimates, the amount of “leverage” (i.e. total debt) on the U.S. consumer’s back, relative to his or her income, is still at all-time highs.

This means that, as consumers get money into their hands, they are more likely to save that money against a rainy day – pretty frightening jobs picture out there – or use it to pay down debt. Neither of those actions is particularly stimulative to the U.S. economy. (This in part assumes that the savings go into a plain-vanilla bank account, as the average consumer is still fairly scared of the stock market.)

Ah, but what about the banks? Even if a consumer just chunks money into a bank account, the bank will lend that money out again, right? Won’t the increased deposit balances at the banks thus have a stimulative effect, causing prices to rise, as the money gets put back into circulation?

Not if the banks are deathly scared to lend…

Hoarding Like Crazy

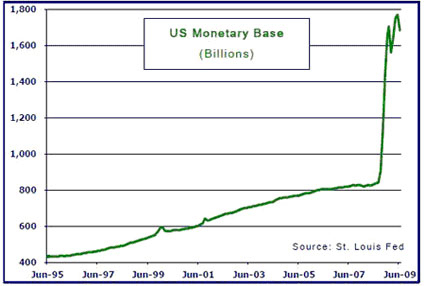

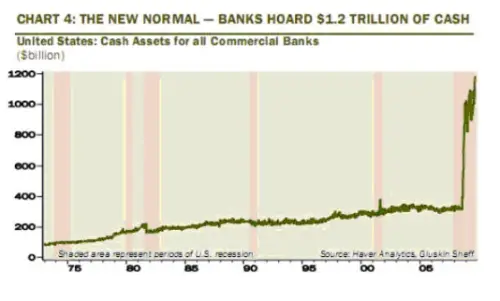

The above two charts from Gluskin Sheff date back 40 years or so. The upper chart shows how commercial bank cash assets rocketed higher in 2008 and 2009. The lower chart shows how lending has contracted dramatically. This is “hoarding” activity in the extreme. Cash goes in to the banks, but doesn’t come out.

Again, remember monetary velocity. How can all that Fed-supplied cash be pushing up prices if it isn’t moving through the system?

Of course, if one believes the banks will eventually start lending out that dough willy-nilly, then one can argue that upward price pressures throughout the economy will eventually result. But eventually ain’t the same as here and now, is it?

If this is the argument –- that a rush of new bank lending will set off the inflationary fireworks show –- then it is also a tacit admission that inflation is not purely a function of printed dollars… it is a function of those dollars changing hands (moving through the system).

The same caveat applies to the belief that foreign central banks will ultimately dump their dollars. For dollars to be dumped on the open market means they change hands. So you see, it’s not just an increase in the money supply. That is only a precursor to a likely later outcome (that shows up with a lag). It’s where the money goes and how fast it gets there that matters.

(Speaking of “changing hands” –- in countries like Venezuela, where inflation is in the 25% range or higher, the idea is to spend your cash as soon as you get it, on whatever you can buy, for fear that its value will rapidly diminish. Cash is the ultimate “hot potato.” You get rid of it as quickly as you can. Is that how U.S. consumers and businesses are acting now? No. We can see, once again, that in countries where inflation is rampant, monetary velocity is the telltale sign.)

Deathly Scared to Lend

Getting back to the banks… some believe it’s only a matter of time before the banks start lending like gangbusters. As soon as the economy shows real signs of stabilizing, that cash is going to come out of the woodwork in the form of new loans, these folks argue. Then we’ll truly see things get hot and prices go nuts.

Is this a reasonable forecast? Your editor isn’t so sure…

The thing is, the banks are scared to lend. In fact, one might argue they are flat-out terrified. There are a few key reasons why banks are still more or less sitting on their hands:

- Few attractive lending risks. Consumers are still in rotten shape. The average small business is poised on a knife edge. Lending to large corporations has a certain attraction, but those guys are flush with cash already (and mostly sitting on it, just like the banks.)

- Banks are making a killing on Treasuries. Thanks to the Fed keeping short-term rates at zero, the banks can borrow at next to no cost, make a leveraged bet on U.S. Treasuries, and earn 15% or 20% on their capital with very little risk (4.5% on long bonds, leveraged a modest 4X or 5X).

- Banks still have gigantic hidden real estate losses on their books!

That last one is the real killer. Few people realize that the situation in residential and commercial real estate (CRE) remains very, very dire… and that banks still have epic hidden losses tucked away in their balance sheets. The financial system game plan of “extend and pretend” has not yet come to its horrible and gruesome conclusion.

In short, the U.S. housing market is being propped up by the U.S. government. This support is proving so expensive, though, that it can’t last forever. Even Uncle Sam’s pockets are finite.

This means that, when the government withdraws its housing support, we will have one of Warren Buffett’s “tide going out” situations. The artificially inflated value of trillions of dollars in residential and commercial real estate assets will fall… legions of tenants, hanging on by the skin of their teeth, will finally go under or be forced out… and the discrepancy between artificial accounting value and true resale value (in some cases “zero”) will be exposed. We will then see to what degree the banks have been swimming naked. And the banks are hoarding cash in part to guard against that fateful day.

This is a big reason, your humble editor believes, why the anticipated bank-lending explosion won’t happen. Much of that excess cash is already committed – to a looming tsunami of losses not yet realized, born of previous excesses not yet worked through.

Meanwhile, where did all that wonderful beautiful government stimulus go? Mostly it went into paper asset prices, not the real economy itself. This is why equity bulls had such a great year in 2009. But for the purposes of this discussion, we are talking about inflation in the real economy, not the paper economy. The link can be very tenuous at times, but the real economy still trumps all in the end. (The economic drag of a bloated financial sector ties in also, but that’s a discussion for another day.)

As Simple As Possible

Einstein (we like to quote Einstein around here) once said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

The goal here is not to complicate things, but to make sure the essential elements are addressed. If you understand that inflation is not an automatic result of an increase in the money supply, but a lagged event depending on how quickly money changes hands, you can then further understand why it sometimes takes a long time for inflation to show up in the system… and you can also see how large amounts of standing debt soak up money like a sponge, retarding both monetary velocity (the critical inflation variable) and prospects for economic growth.

This understanding helps cultivate useful traits like patience on the investing side and creative flexibility on the trading side. If the dollar goes up (and gold down) for a bit longer than one might expect – or, even more perplexingly, if the financial press starts talking about falling prices and wages this year, even as the Fed keeps pumping – now you’ll (hopefully) have a better sense of why.

The end game may indeed be accelerating monetary velocity, a knock-on rise in prices, and a spectacular loss of faith as the desire for dollars plummets… but there could be a ways to go before this happens.

Justice Litle, Editorial Director, Taipan Publishing Group

The following links were added 7/26/2022 and will contain more recent information.

Read More…

Would love an update for 2022

Although we haven’t updated this post we have updated our other article on the Velocity of Money located here