The Fed funds rate is, effectively, the price of money. When it changes, much like dropping a rock into the water, the impact ripples out in all directions.— Greg McBride, Bankrate Chief Financial Analyst

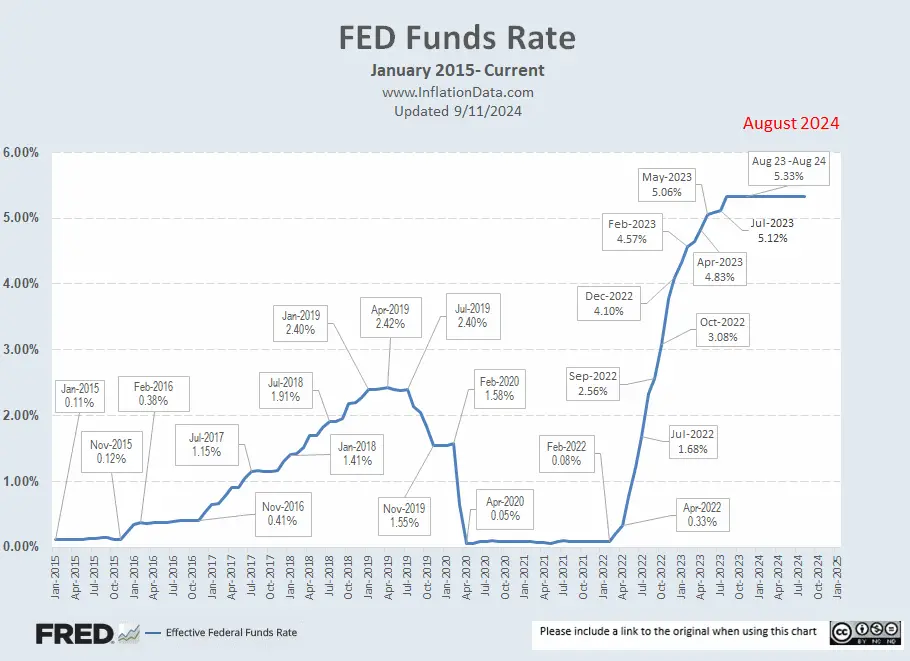

On Wednesday, September 18th, the FED reduced interest rates for the first time in four years. Mr. Market has been anticipating this cut all year and it finally happened. Last month FED Chairman Powell hinted at a rate cut at this FOMC meeting and at the time most experts believed that the cut would only be 25 basis points or ¼%. But, once lower-than-expected August inflation numbers were released on September 11th, the market began clamoring for a 50 basis point cut, or even a 75 basis point reduction. In addition, the market wanted further reductions in November and December as well. There has also been talk that the FED has waited too long to act (again) and so a recession is in the making.

On Wednesday, September 18th, the FED reduced interest rates for the first time in four years. Mr. Market has been anticipating this cut all year and it finally happened. Last month FED Chairman Powell hinted at a rate cut at this FOMC meeting and at the time most experts believed that the cut would only be 25 basis points or ¼%. But, once lower-than-expected August inflation numbers were released on September 11th, the market began clamoring for a 50 basis point cut, or even a 75 basis point reduction. In addition, the market wanted further reductions in November and December as well. There has also been talk that the FED has waited too long to act (again) and so a recession is in the making.

With all of that in the background, the FED decided to go with a 50 basis point reduction in the FED Funds rate. Although the actual rate has held steady at 5.33% over the last year, the FED has had a target of 5.25% to 5.5%. So, a “Jumbo” 50 basis point reduction takes the FED target down to 4.75% to 5%.

The federal funds rate is the FED’s main benchmark interest rate that ripples through the U.S. financial system and indirectly influences how much consumers pay to borrow and how much they’re paid to save.

The FED funds rate filters out through the rest of the economy because it’s the interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight lending.

The FED funds rate filters out through the rest of the economy because it’s the interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight lending.

If banks need to borrow money from other banks the FED Funds rate (FFR) helps determine the rate banks charge each other. Banks can’t charge each other more than the upper limit of the FED Funds Rate because the borrowing bank would just borrow from the FED’s Discount Window at the FFR instead. The FED charges the upper limit because it prefers that banks borrow from each other rather than from the FED directly but the FED is the “Lender of Last Resort”.

When a bank loans another bank money “overnight” they are actually loaning the money that is on deposit at the Regional Federal Reserve banks (a simple notation is made).

When a bank loans another bank money “overnight” they are actually loaning the money that is on deposit at the Regional Federal Reserve banks (a simple notation is made).

The average charge on these loans is called the Effective FED Funds Rate. When the FED “Adjusts Interest Rates” it causes the banks to raise or lower their individual rates charged to each other accordingly. This has a snowball effect on all interest rates in the economy.

Two Different FED Systems

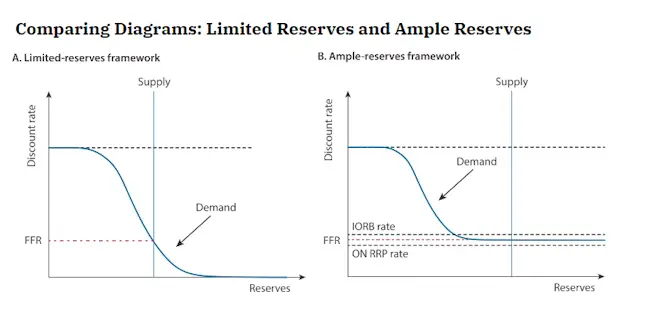

Prior to the crash the FED operated on a “Limited-Reserves” Framework which tried to affect interest rates by adjusting the supply of reserves but after 2008 the FED shifted to an “Ample-Reserves” Framework that adjusts the Interest Rates paid to banks. In the new model reserves (i.e. supply) is virtually unlimited and the FED Funds Rate is limited by the Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) at the high end and the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (ON RRP) Rate on the low end. Looking at the two systems side-by-side we can see how the FFR could end up the same but by different methods. The difference is that the new system will work even if the Discount rate is at or near zero. Under the old system if the discount rate went to zero the demand was also zero and the problem was called “pushing on a string”. Under the new system even if the discount rate goes to zero there will still be some demand.

Prior to the crash the FED operated on a “Limited-Reserves” Framework which tried to affect interest rates by adjusting the supply of reserves but after 2008 the FED shifted to an “Ample-Reserves” Framework that adjusts the Interest Rates paid to banks. In the new model reserves (i.e. supply) is virtually unlimited and the FED Funds Rate is limited by the Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) at the high end and the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (ON RRP) Rate on the low end. Looking at the two systems side-by-side we can see how the FFR could end up the same but by different methods. The difference is that the new system will work even if the Discount rate is at or near zero. Under the old system if the discount rate went to zero the demand was also zero and the problem was called “pushing on a string”. Under the new system even if the discount rate goes to zero there will still be some demand.

Up until the pandemic, banks were required by law to keep a certain amount of reserves on hand at one of the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks and the FED paid interest on that money. This requirement was necessary under the limited reserves system but became irrelevant under the new system so it was abolished.

Images courtesy of the Federal Reserve (FRED)

For more information See:

The FED’s New Monetary Policy Tools- St. Louis FED

More FED related Articles on InflationData

Hi Tim,

I hope you’re keeping well and not working too hard!

I was wondering if you think that life could be considered to be a Giffen good?

Yours with best wishes,

James

James,

I would hate to put a price on a life especially a low price. I believe that the most valuable thing on earth is a Human Life. Unfortunately, society has devalued this devine gift to become almost worthless. And in fact, has made it a detriment rather than a blessing.

Thomas Jefferson said, “The care of human life and happiness and not their destruction, is the first and only object of good government.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupery put it this way, “Even though human life may be the most precious thing on earth, we always behave as if there were something of higher value than human life.”

J. K. Rowling said,

“We’re all human, aren’t we? Every human life is worth the same, and worth saving.”