The short answer is because the U.S. Federal Reserve Board, i.e., the “FED,” says it is. The longer answer is much more complicated. To determine whether 2% is really best for you, we will have to look at a variety of different factors.

First of all, it might surprise you to know that it wasn’t always that way. It wasn’t until January 25th, 2012, that U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke set a 2% target inflation rate. Before that, the FED didn’t have a specific inflation target but instead regularly set a target range. This range was often between 1.7% and 2%. But even that range is relatively new, and some economists still believe that Zero percent inflation is optimal.

Prior to 1979, the FED didn’t target inflation at all. Instead, the FED’s policy panel, i.e., the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), set a target FED Funds Rate and tried to maintain that rate through purchases and sales of Treasury Securities on the open market. The FED was also more secretive about the actual rate that they had chosen (i.e., they didn’t announce it like they do today). So, the financial analysts would monitor the FED’s actions and try to discern the FED’s intent.

Inflation Encourages Spending

Some economists think that “a little inflation is good” because it encourages spending. As consumers end up with a few extra (inflated) dollars, they are encouraged to consume more. This excess consumption boosts the economy and encourages those who receive the additional money also to spend more. Eventually, however, the consumers will realize they don’t have more purchasing power, simply more dollars (since it now takes more dollars to buy the same amount of goods). This results in consumers having spent more than they rationally would, had they realized the true cost of their purchases.

So, at its core, inflation is dishonest since its primary benefit is based on deception.

Once consumers realize the deception, they will have to reduce spending below what they would have to balance the equation. If they don’t, they will get further into debt. This inflation-inspired overspending, followed by austerity, results in the boom-bust economic cycle. If the FED persists in trying to create perpetual prosperity, they will have to pump ever more liquidity into the economy, eventually resulting in hyperinflation. Hyperinflation will eliminate the debt and allow the economy to reset but will cause severe financial pain in the meantime.

Inflation Reduces Debt

Another advantage of inflation is that it benefits debtors. Over time as inflation erodes the purchasing power of a currency, people have more dollars, so it is easier to pay off a debt denominated in a fixed number of dollars. So, inflation encourages debt since it will be easier to pay off as time goes on. Although you would think this would hurt bankers, they have devised ways to avoid the long-term effects by passing off the debt to “the market” and government programs like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Instead, the bankers benefit by having an increased number of debtors addicted to their easy money.

History of the FED’s Inflation Targets

Back as early as the 1940’s the FED was tasked with multiple and often conflicting goals. Over time these goals have shifted with differing emphasis on which objective should be paramount. At the end of WWII, with millions of soldiers returning home, unemployment was the major problem. So Congress, with the depression of the 1930s fresh in their minds, declared a goal of reducing unemployment. So the FED was tasked with expanding the supply of money and credit so that “in no event will a credit crunch occur”.

With the primary goal of avoiding a credit crunch and promoting employment, the FED created massive inflation. But in those days, the U.S. Dollar was “pegged” to a fixed amount of gold. If other countries felt that there were too many paper dollars floating around versus the gold backing it, they could request payment in gold instead of paper. With inflation over 6% in the early 1970s, that is precisely what happened as France demanded gold payment. Nixon feared that this would deplete U.S. gold reserves, so he “closed the gold window” and discontinued Dollar to gold convertibility. This resulted in currencies floating in value against each other rather than being convertible into gold. Another result was the legalizing of individual gold ownership. See Oil, Petrodollars, and Gold for more information.

The FED’s Dual Mandate

In 1976, Congress debated the Humphrey-Hawkins Act, which stated that “Within five years, unemployment should not exceed 4 percent… and inflation should be reduced to 3 percent or less, provided that its reduction would not interfere with the employment goal. And by 1988, the inflation rate should be zero.” So, when inflation rose above 5%, Congress (and the public) saw even 2% inflation as too much. This new view of low unemployment combined with low inflation became known as the FED’s “Dual Mandate”.

How to achieve the Dual Mandate?

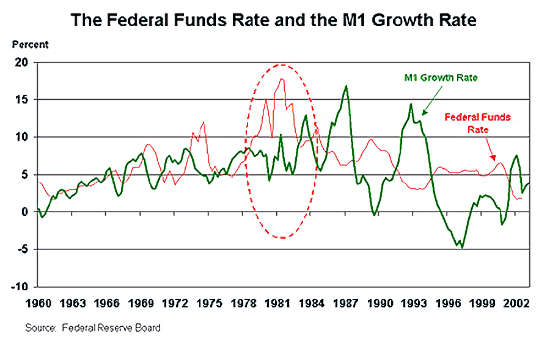

During the 1970s, the money supply, i.e., M1 and the FED Funds rate, became disconnected… controlling the FED Funds Rate no longer worked, so a new policy became necessary.

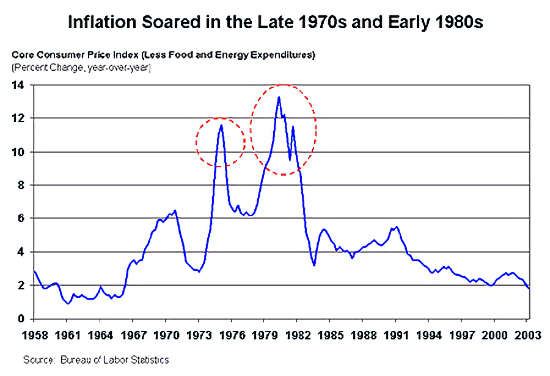

In October 1979, with annual inflation over 12%, FED Chairman Paul Volcker introduced a new policy, but even then, it was not to target a specific inflation rate. Instead, it targeted the quantity of money—specifically nonborrowed reserves, i.e., financial institutions’ assets not borrowed from the FED.

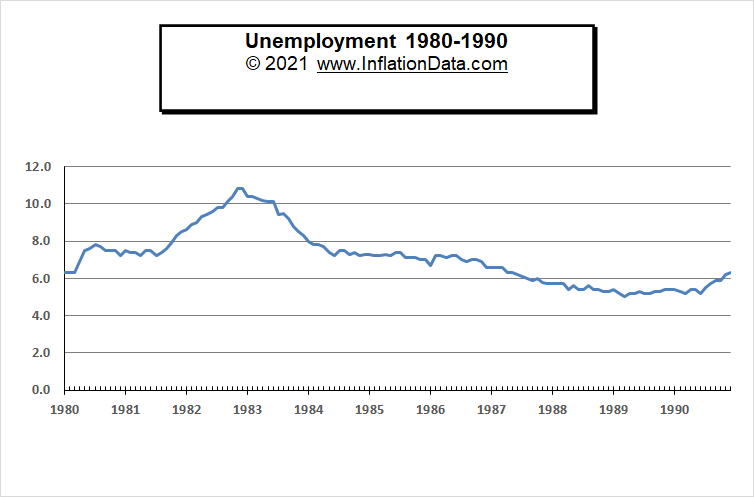

Inflation during the 1980s fell somewhat but still hovered around 5%. And the FED once again shifted its policy back toward controlling “the price of money,” i.e., the FED Funds rate, rather than the quantity of money. During this time, the FED considered fighting inflation more important than promoting employment. Despite that, getting inflation under control also helped the employment situation. Unemployment in December of 1982 peaked at 10.8% and had fallen to 5.0% by March 1989. So, from this, we can see that higher inflation doesn’t always translate into more employment. Instead, a healthy economy translates into higher employment. Initially, inflation can stimulate the economy, but (like with any drug) getting a “new high” takes more and more.

The FED Chooses 2%

The FED Chooses 2%

In the wake of the 2008 market crash, with the memory of the 2009 deflation once again paramount, FED Chairman Ben Bernanke took the opportunity to set a 2% target inflation rate on January 25th, 2012. At the time, inflation had already rebounded to 2.93% from a low of -2.10% in July 2009. But not all economists agree that 2% is optimum. William Poole – Economist and President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (1998–2008) felt that 0% was the best inflation rate.

What’s so Bad about Deflation?

When deflation hit in 2009, the FED panicked and began a media blitz about the dangers of deflation. But what’s so bad about deflation? Wouldn’t people rather have prices go down instead of going up? The natural state of affairs is actually deflation… as we can clearly see in the computer industry. New advances and competition drive prices down and quality up, so why fear deflation? During the late 1800s, the industrial revolution dramatically increased productivity resulting in falling prices and increased prosperity of the masses. Thus if deflation is the result of increased productivity, it can be a good thing.

The problem occurs when deflation is not caused by competition and advances but by monetary collapse. The stock market crash eliminated trillions in wealth, thus massively contracting the money supply. The crash forced people to cut back on purchases, which snowballed into companies laying off employees, which resulted in more reductions in purchases, etc. But what isn’t mentioned was that massive artificial increases in liquidity created the market bubble in the first place. So, inflation itself was what caused the need for more inflation.

The Problem with Deflation

The reason that the FED fears deflation is not for the good of the people but for the sake of the government. You see, although deflation helps buyers, it hurts debtors. Inflation allows debtors to repay their loans with “cheaper dollars,” and hyperinflation will wipe out debt altogether. Conversely, deflation makes paying back debt more difficult as each Dollar becomes more valuable than the original Dollar borrowed.

And who is the largest debtor in the world? The U.S. government.

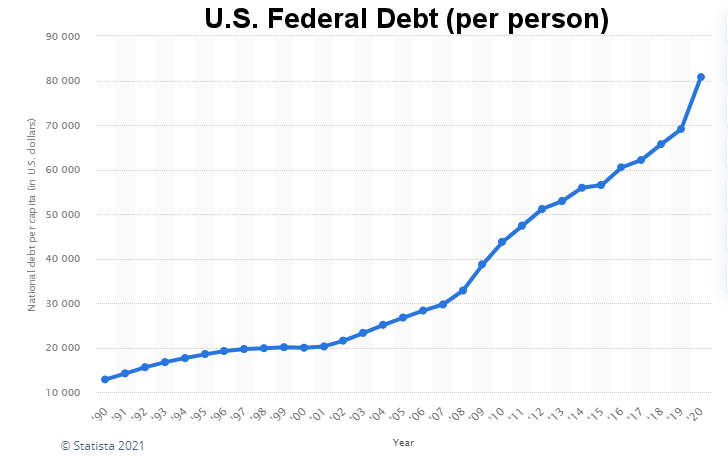

So repaying all that debt with more expensive dollars would cause a collapse in the government’s debt house of cards. In addition, America has increasingly become a nation of debtors, with the average per capita debt increasing. In years past, those under the age of 25 had virtually zero debt, but Gen Z (ages 18 to 23) is already $16,043 in debt. The average American has $90,460 in debt, which includes all debt, including mortgages, credit cards, and student loans. The typical American household has an average debt of $145,000 with a median household income of $79,900. Average Americans with all that debt don’t mind a little inflation to help them out of the hole.

But when consumers see prices rising weekly at the gas pumps and the grocery store, they forget that it is becoming easier to pay off their credit cards and mortgages.

In years past, families valued having less debt, and so inflation was more detrimental.

Who Does Inflation Hurt Most?

When we first think of inflation, we assume that it will affect all people equally. After all, if everyone is using the same dollars, wouldn’t everyone be affected equally? The truth is that everyone isn’t affected equally. As we saw, inflation helps (and deflation hurts) those with a lot of debt. Conversely, inflation hurts lenders since they get paid with depreciating dollars. Modern banks have offloaded much of that cost by selling their mortgages on the open market, but someone still bears the lending cost.

When we first think of inflation, we assume that it will affect all people equally. After all, if everyone is using the same dollars, wouldn’t everyone be affected equally? The truth is that everyone isn’t affected equally. As we saw, inflation helps (and deflation hurts) those with a lot of debt. Conversely, inflation hurts lenders since they get paid with depreciating dollars. Modern banks have offloaded much of that cost by selling their mortgages on the open market, but someone still bears the lending cost.

Inflation also hurts wage earners who, even though they may get a cost-of-living raise, won’t get it until next year. Thus they will have suffered through a whole year of price increases before getting a wage increase. And next year, they will be another year behind, so over the long run, the average consumer falls further and further behind on most bills but gets a slight reprieve on his mortgage. But for low-income renters, all they see is the increase in the cost of living… they do not get the offsetting benefits of a cheaper mortgage.

Inflation also hurts savers. Typically the argument is phrased like this: “If you’re holding cash in your drawer or under your mattress and prices rise and rise, then that cash gets less and less valuable. So, it’s actually a tax on cash holdings.” But that phrasing is slightly biased because, after all, “who holds cash under their mattress?”. But the fact is “cash” is not just greenbacks under the mattress. “Cash” also includes money in savings, checking, and other readily available accounts. Even if those accounts pay interest, they don’t pay enough to compensate for the inflation. For instance, if you earn ½%, but inflation is 2%, you are still losing 1 ½% EVERY YEAR. If inflation is 5%, you are losing 4 ½% per year. And in addition to the inflation “tax”, you have to pay income taxes on the interest even though you are actually losing value.

Inflation also hurts the elderly. Inflation is especially harmful to those on “fixed incomes” since their expenses increase, but their income isn’t. For this reason, Congress passed a law indexing Social Security to the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Workers (CPI-w). Still, the CPI-w index is often lower than the CPI-e, an experimental index that more accurately represents the costs Senior Citizens experience, such as healthcare.

For more info, See: Who does inflation hurt most?

Conclusion:

Two percent inflation was an arbitrary choice by the FED as recently as 2012 based on their cost-benefit analysis. But their analysis factors in the benefit to the government and not just to citizens. Part of their consideration is also “how much inflation could they get away with, to reduce the government debt”. They also considered that many “cash holders” were either drug lords or foreigners, so reducing the value of their cash holdings was not a concern.

Individuals each have their own personal inflation rate based on the goods they consume. Whether inflation helps or hurts them depends on their individual circumstances, including debt levels and income types.

You might also like:

- What’s so bad about deflation?

- Who does inflation hurt most?

- Oil, Petrodollars, and Gold

- Inflation during the 1980s

- How Does Gold Fare During Hyperinflation?

- How paper money fails

- What is Inflation?

- Which is Better: High or Low Inflation?

- What is the Money Multiplier?

- What is the velocity of money?

- Inflation and Velocity of Money

Leave a Reply