I recently answered this question on Quora. And I thought I would share an expanded answer with you as well.

Whenever a question starts with an assumption you need to examine whether that assumption is in actuality true. If the assumption is vague enough it can be fairly difficult to determine and we might be tempted to go with the basic assumption. In this case, the assumption is that “everything” “big” is increasing in price faster than average. We have no clue what he means by “everything” (I’m sure he isn’t being literal) and what does he mean by “big”? Large as in houses, and cars, or expensive like Yachts and Lamborghinis, or things that are a large portion of the average person’s budget? We don’t know but I will take a stab at an answer. ~ Tim McMahon, editor

First of all, this question is based on a logical fallacy. The inflation rate (CPI-U) is calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics every month and is the average of all prices, so if “everything big” is increasing in price faster than “inflation” (i.e. the average of everything) then “everything small” must be increasing in price slower than the average. After all, that is what makes it an “average”.

How the Inflation Index is Calculated

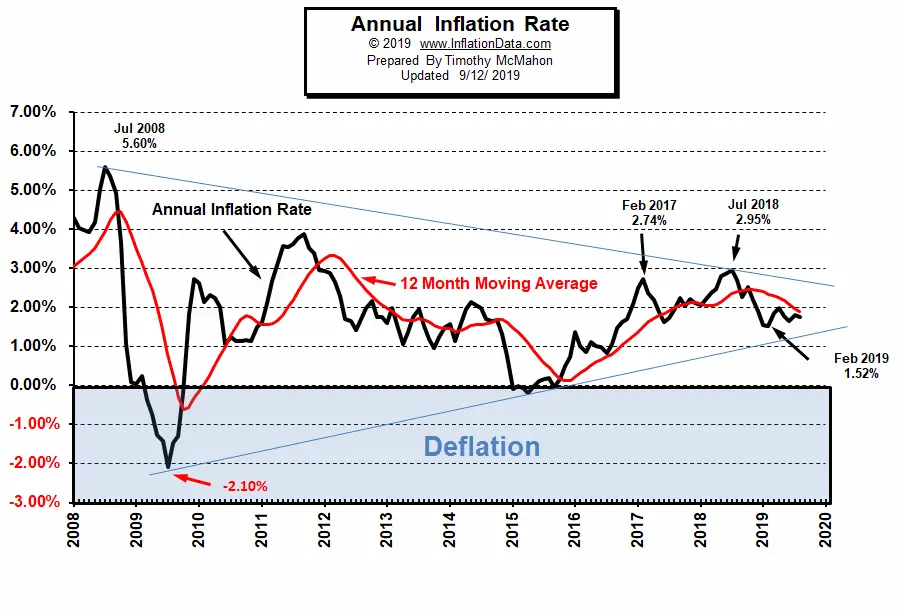

Every month the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) surveys about ten thousand prices all over the country and generates the CPI or (Consumer Price Index). Then it compares last month’s index to this month and calculates the percent difference. That is the monthly inflation rate. They also calculate the difference compared to a year ago (this is the commonly quoted “inflation rate”).

It Isn’t an Ordinary Average

But they don’t just average all the prices equally, they weight them based on how much of them the average person buys. The average would be pretty useless if it gave equal weighting to gasoline and milk even though they may be close in price per gallon, the average family buys much more gasoline than they do milk.

The CPI-U is weighted based on how much the average urban consumer buys. The BLS has other averages for other demographics. But the CPI-U is the most commonly quoted one.

So if you are asking why “big” items like Yachts and Lamborghinis are increasing faster than small items like toasters and bread that is possible because not many average urban consumers buy them. So they play a very small part in the overall CPI-U. Perhaps they are weighted to 1/100th of 1% of the total or something.

In this PDF document by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we can see that Food and beverages are weighted at 14.649% for the CPI-U, Housing is 42.634%, Apparel is 3.034%, Transportation is 15.318%, Medical Care 8.539%, Education 3.209%, Recreation 5.66%, etc. and each of those is broken down further into Cereal, Meat, Dairy, Gasoline, Electricity, Used Cars, New Cars, etc., and those are broken down even further. So the actual “Inflation Rate” is a weighted average of all of them.

Are You an Average Consumer?

But you might not be an average urban consumer (actually you most likely aren’t) do you drink the same amount of beer and smoke the same amount of cigarettes as the average person? Do you eat as much meat and fish as the average? Do you drive an average car? Do you go to the Doctor the same amount as the “average person”?

Probably not, so the CPI-U will not be the same as your personal inflation rate but it should be relatively close.

There is also the issue of Selection bias such as when we buy a car, we tend to notice similar cars more often than we did before. Thus we seem to think the things we buy are increasing more than other things.

Now if you are wondering if we can actually trust the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics that is a different question.

See: Can We Trust Government Inflation Numbers?

You might also like:

- What is the Real Definition of Inflation?

- What is the Current U.S. Inflation Rate?

- How Do I Calculate the Inflation Rate?

- What is Core Inflation and Why Doesn’t It Include Food and Energy?

Leave a Reply