There are three major categories of problems that can cause bank instability. In his article “A Tale of Two Crises“ Bloomberg’s John Authers tells us that they are:

- a liquidity crisis- When customers pull their money out.

- a solvency crisis- When borrowers can fail to repay their loans.

- a confidence crisis- When shareholders sell the bank’s stock, sending their shares down making it harder to raise money.

And beyond true crises, changes in economic and financial conditions can attack their profits — which is bad for shareholders and ultimately might tend to imperil everyone connected to the bank.

Understanding a Liquidity Crisis

One of the primary causes of a Liquidity Crisis is a mismatch between the maturity of assets and liabilities, or of properly timed cash flow. Although liquidity problems can affect a single institution, it becomes a true liquidity “crisis” when systemic factors create a simultaneous lack of liquidity across many institutions or the entire financial system.

According to Investopedia:

Banks and financial institutions are particularly vulnerable to this kind of liquidity problem because much of their revenue is generated by lending long-term on loans for home mortgages or capital investments and borrowing short-term from depositors’ accounts. Maturity mismatching is a normal and inherent part of the business model of most financial institutions, and so they are usually in a continual position of needing to secure funds to meet immediate obligations, either through additional short-term debt, self-financed reserves, or liquidating long-term assets.

A lack of confidence in a bank (or the banking system as a whole) can cause depositors to withdraw their money resulting in a liquidity crisis for the bank(s).

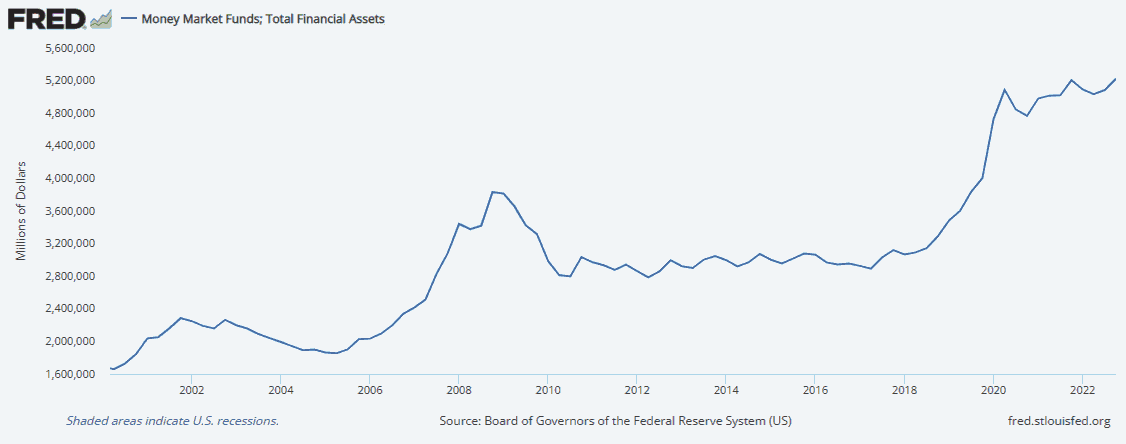

The FED’s recent tightening has created problems for banks due to rising interest rates, which have caused short-term rates to rise faster than long-term rates. This created an “inverted yield curve” and encouraged depositors to shift funds from their bank accounts to higher-yielding money market accounts.

So far, the shift has primarily affected the smaller banks, with the money flowing in part to the larger institutions that — thanks to the more conservative regulation forced on them after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 — are obliged to hold more capital, and who also tend to hold a smaller proportion of their liabilities in uninsured deposits. Making the problem worse is the ability to process these transfers virtually instantly with a few mouse clicks.

Why a Solvency Crisis is Different

According to Investor’s Chronicle:

“In simple terms, liquidity is a measure of ‘flow’: does an institution have enough short-term funds on hand to meet its immediate financial obligations and avoid default?

Solvency, on the other hand, is a ‘stock’ measure, and requires an institution to be able to pay its debts over the medium and long term. To be solvent, an institution’s assets need to exceed its liabilities.”

So even if a bank is “solvent” it may not have enough cash on hand to be “liquid”.

Typically a “liquidity crisis” is easier to fix. Since the central bank acts as a lender of last resort, it can inject liquidity into the system in times of stress in order to stem the outflow. So, if the FED knows a bank is solvent it can loan it enough cash to get through its liquidity problem.

On the other hand, a “solvency crisis” can be worse. In this case, if the value of an institution’s assets falls below that of its liabilities, it is technically bankrupt. This creates financial losses that have to be borne somewhere in the system. Under a free market system, these losses should be borne by the stockholders of the bank. But recently we have seen a trend toward shifting these losses to the public. In the long run, this will result in banks actually taking more risks as we said in Central Banks Respond Differently to the Banking Crisis, “Banks not disciplined by their depositors and not at risk for deposit flight are dangerous institutions. They leave bank executives free to swing for the fences on the asset side of their balance sheets without fear that attentive depositors will move their money to safer pastures.”

If bank losses are to be borne by the public, stricter lending requirements and more oversight is required in order to prevent the long-term collapse of the banking system.

A Confidence Crisis

From Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English:

A Crisis of Confidence is “a situation in which people no longer believe that a government or an economic system is working properly, and will no longer support it or work with it.”

-

Bank runs occur when a bank faces a loss of confidence, sparking many customers to withdraw their deposits.

-

Massive withdrawals happening simultaneously put the bank’s existence at risk.

-

This creates fears and contagion can spread from one institution to another, undermining the banking system as a whole.

-

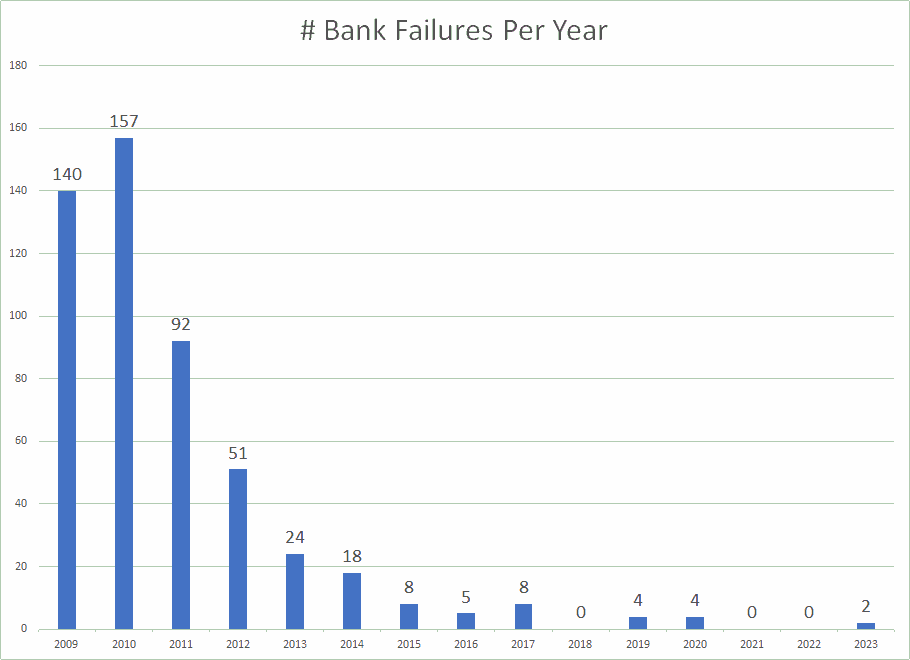

Businesses and consumers around the world are generally better protected from bank failures now, compared with the financial crisis of 2008, due to stricter legislation.

-

Even so, not all of the rules apply to smaller banks and some portions of the legislation have been rolled back.

According to the World Economic Forum,

“When everything’s going well, you have confidence in your bank, everything is fine and there’s nothing to worry about. Take away just a little of that – perhaps you see a tweet that your bank might be in difficulty or a news report that it’s been amassing bad assets – and you risk a loss of trust in the whole financial system.”

According to the FDIC:

- Central Banks Respond Differently to the Banking Crisis

- Stock Market Ignores Lower Inflation in February

- How Loose Monetary Policies Cause Recessions

Leave a Reply