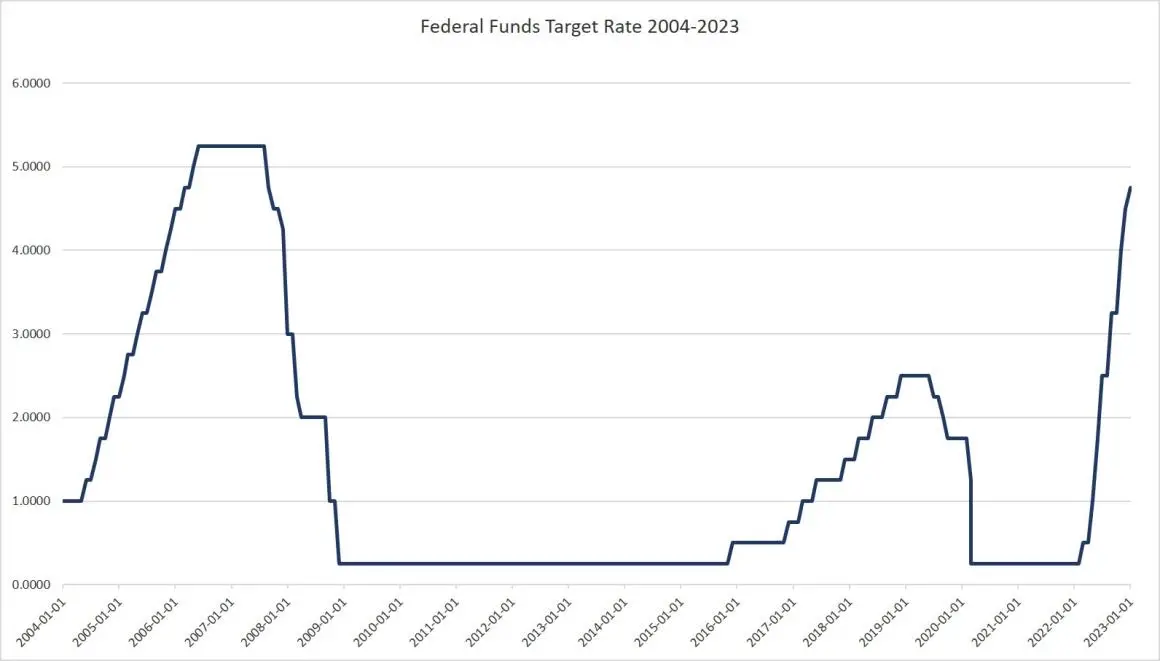

The Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on Wednesday raised the target policy interest rate (the federal funds rate) to 4.75 percent, an increase of 25 basis points. With this latest increase, the target has increased by 4.5 percent since February 2022, although this latest increase of 25 basis points is the smallest increase since March of last year.

Indeed, the FOMC has slowed its rate of increase over the past three months. After four 75 basis point increases in 2022, the committee approved a 50-point increase in December, followed by the 25-point increase this week.

In other words, the FOMC has been slowed down in its monetary tightening. The committee was careful to deny that it plans on ending or reversing rate increases, however. In its press release, the FOMC noted:

The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.

Of course, the FOMC’s publicly stated predictions of its own future behavior are essentially useless as accurate predictors of future events. This has been illustrated over and over. For example, a year ago, not a single member of the FOMC predicted that the target rate would rise above 4 percent in either 2022 or 2023. By September 2022, every member but one had switched to predicting that a rate above 4 percent would be necessary to bring down inflation. This came after years of flat denials that the Fed would raise the target rate at all through 2023 and that inflation was “transitory.” Of course, these predictions proved to be so wrong that the Fed abandoned forward guidance in 2022, and the FOMC embraced a month-by-month strategy of guessing a new target rate each month. In other words, they’re making it up as they go.

So, the fact that the FOMC is now saying it will keep raising rates means nothing in the sense that there’s no reason to believe this information is even reliable. It’s entirely possible the committee will raise rates again. But, given the information we have, it’s also just as likely that they won’t. We won’t know until the next meeting.

The committee also predicted:

The Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans. The Committee is firmly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.

Predictions of what the FOMC plans to do with the portfolio are even more volatile and unreliable, given that changes in the portfolio tend to get less attention in the press. As an example of the Fed’s lack of any real plan for the portfolio, we can remember that in 2019, the Fed was also “committed” to “normalizing” the portfolio. Yet it quickly became clear in late 2019 that the economy was too weak to tolerate much quantitative tightening at all, and soon the Fed was back to buying up more assets yet again.

This disconnect between Fed predictions and reality also extends to the economy. Let it not be forgotten, for example, that months after the Great Recession had already begun, Ben Bernanke was still predicting there would be no recession in 2008. These elite forecasting “skills” were on display in the second half of 2021 as well: inflation began to surge above 5 percent, but the Fed did nothing and said it was all transitory.

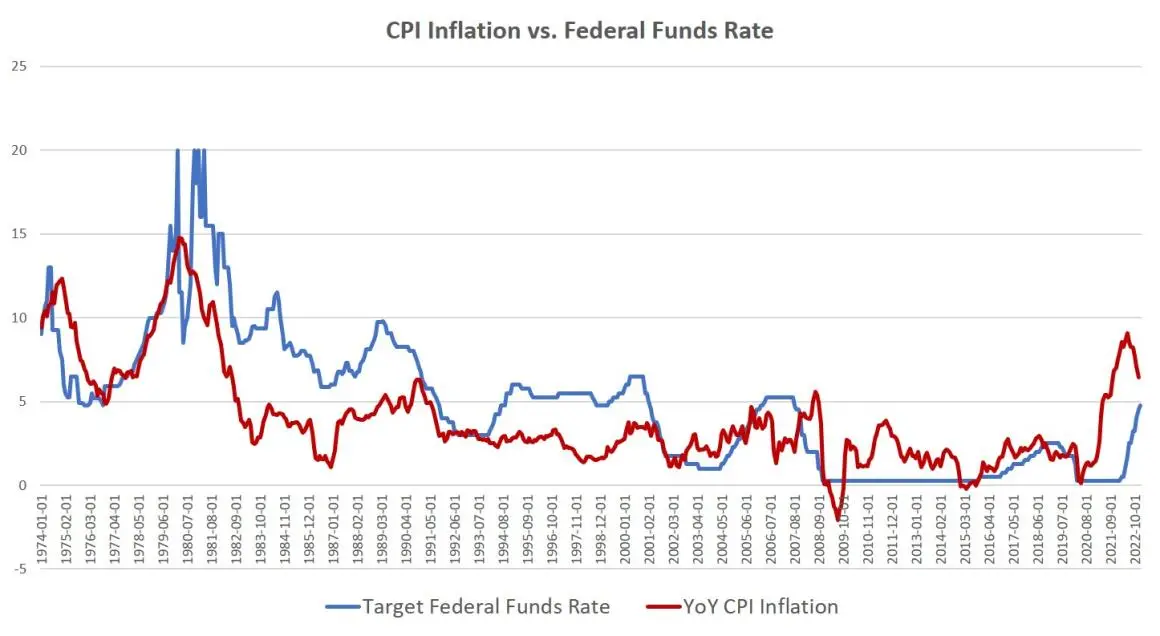

Note, for example, how Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation began to surge in July 2021 and yet the target rate remained at 0.25 percent for eight more months. The Fed was so behind the curve on inflation that even after raising the target rate by 450 basis points, it is still well below the CPI inflation rate.

Considering the circumstances, monetary policy is still remarkably loose.

It’s best to think of these FOMC predictions as little more than an exercise in public relations and as part of an effort to remove market froth without actually raising the target rate or reducing the size of the portfolio, which we’ve seen is generally too much for the easy-money-addicted market to stomach.

This is all part of the plan to engineer a “soft landing.” So, at the FOMC press conference on Wednesday, as part of this dog-and-pony show, Jerome Powell repeatedly emphasized that the Fed plans to keep raising rates and that it won’t stop until “the job is done.” The basic intended takeaways from Wednesday’s meeting included:

- The Fed can’t yet declare victory over price inflation.

- Disinflation in some areas has begun, but non-housing services have yet to see slowing prices.

- More rate hikes are in store.

- No cuts in the target rate are planned for this year.

- A “soft landing” is still very much possible.

Powell stuck doggedly to this message in spite of a multitude of repetitive and tired questions from the reporters in the room that essentially amounted to “Why haven’t you stopped raising rates, and when will you?”

Yet it appears that, in spite of Powell’s cross-my-heart-and-hope-to-die claims, the markets expect the Fed to stop raising rates and then bring rates back down in coming months. This could be seen in the fact that the S&P 500 began to surge on Wednesday almost as soon as Powell started talking.

So, if Powell was hoping to send a hawkish message while also reducing rate increases to 25 basis points, he apparently failed, and Kathy Jones is probably right:

Seems like Powell flubbed this one. Meant to send a cautious, hawkish message but ended up doing the opposite.

—Kathy Jones (@KathyJones) February 1, 2023

On the other hand, Powell is right about one thing. He emphasized in the press conference that the full extent of the Fed’s (mild) tightening in 2022 has yet to be felt. The economy has been so fragile and so based on little more than easy money since 2006, that it only takes some minor tightening to throw a major monkey wrench into financial markets—and then the larger economy.

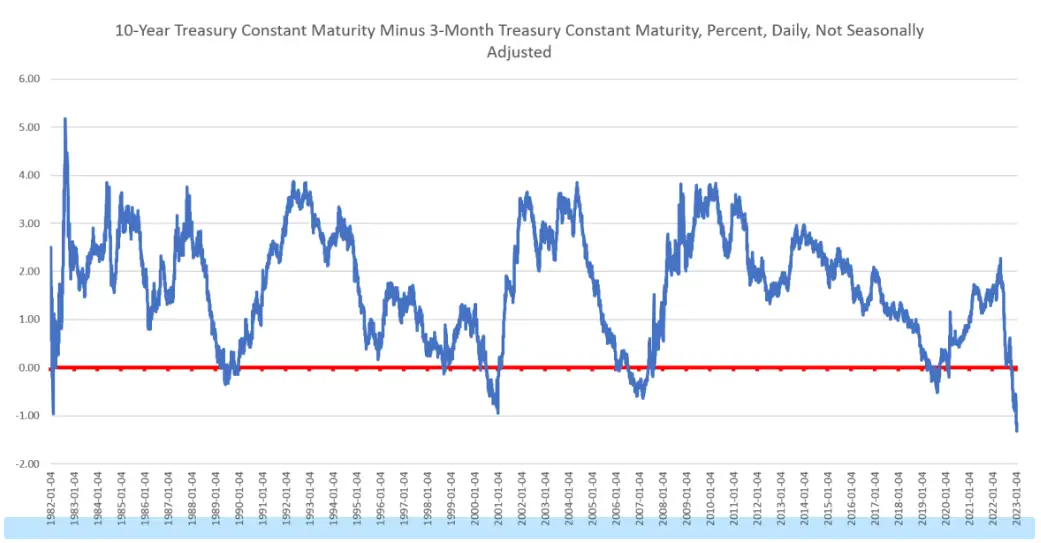

Indeed, the signs of recession are everywhere. Money supply growth actually turned negative for the second month in row a in December. The yield curve is more inverted now than it’s been in forty years. Home prices are slowing. The Leading Economic Index is well into recessionary territory. Powell apparently believes this is just the beginning.

So, if Powell is right about the lagging effects, the economy will more obviously be in dire straits soon and the Fed will embrace easy money. Unfortunately, if the lagging effects are just now getting warmed up, both Powell and markets are wrong to keep hoping for a “soft landing” (whatever that even means). At this point, employment is the only major economic indicator that looks “good,” although real wages have been falling for nearly two years.

This leaves two likely scenarios. One is that Powell is actually telling the truth and the FOMC is not going to stop raising rates until price inflation really is back to the arbitrary 2 percent standard. That will have to mean a real recession with real monetary deflation for more than a month or two. The other is that if the Fed does panic and jump back to easy money at the first sign of a surging unemployment rate, that will probably mean a second wave of inflation, as occurred in the late 1970s, when Arthur Burns tried the same easy way out for the Fed. And, as in the late seventies, inflation may also come with ongoing economic stagnation. Powell pretty clearly wants to avoid being another Burns, but it’s unclear if he can pull it off.

About Ryan McMaken

Ryan McMaken is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Ryan has a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. Ryan is a cohost of the Radio Rothbard podcast, has appeared on Fox News and Fox Business, and has been featured in a number of national print publications including Politico, The Hill, Bloomberg, and The Washington Post.

Ryan McMaken is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Ryan has a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. Ryan is a cohost of the Radio Rothbard podcast, has appeared on Fox News and Fox Business, and has been featured in a number of national print publications including Politico, The Hill, Bloomberg, and The Washington Post.

Leave a Reply