By John Steele Gordon

Author, An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power

Money is just another commodity, no different from petroleum, pork bellies, or pig iron. So money, like all commodities, can rise and fall in price, depending on supply and demand. But because money is, by definition, the one commodity that is universally accepted in exchange for every other commodity, we have a special term for a fall in the price of money: we call it inflation. As the price of money falls, the price of every other commodity must go up.

And what causes the price of money to fall? The answer is very simple: an increase in the supply of money relative to other goods and services. As the Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman explained, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Inflation has been around almost as long as money itself. In the disastrous third century, inflation wracked the Roman Empire as emperors, unable to pay the bills, increasingly debased the coinage. The once proud silver denarius became a copper coin only thinly plated in silver. Roman merchants demanded more and more denarii in exchange for goods as the coin’s intrinsic value declined.

Only when Emperor Diocletian, who ruled from 284 to 305 A.D. and was one of the great men of late antiquity, reformed the taxation and coinage systems, did a degree of economic stability return to the Roman world.

In the sixteenth century, as the gold and silver pouring into Spain from the New World caused a rapid rise in the European money supply relative to the production of goods and services, prices rose about 400 percent over the course of the century.

There was no inflation in the American colonies for the simple reason that the money supply was only a hodgepodge of foreign coins (most commonly the Spanish dollar), tobacco warehouse certificates, beaver and deer skins, wampum, and paper money printed by the colonial governments. Much trade was conducted on a barter basis.

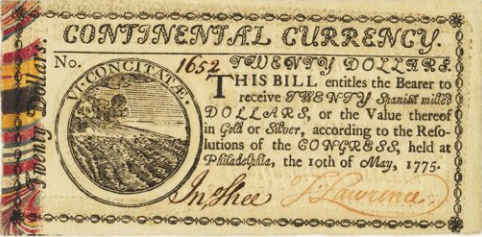

But when the American Revolution began, both the new state governments and the Continental Congress had to find ways to finance it. Having limited ability to borrow and to lay taxes, they quickly began printing money.

But when the American Revolution began, both the new state governments and the Continental Congress had to find ways to finance it. Having limited ability to borrow and to lay taxes, they quickly began printing money.

As “fiat money”—money that is money only because the government says it is money—always does, the so-called “continentals” depreciated rapidly in value, becoming essentially worthless by the end of the Revolution. The phrase “not worth a continental” became part of the American lexicon for more than a century.

Between 1775 and 1779, the Continental Congress issued no less than $225 million in continentals, a huge sum relative to the size of the American economy. Prices doubled in 1776 and doubled again in both 1777 and 1778. By 1781, prices were up 80-fold relative to the continental.

In addition to the problem of fiat money, the Continental Army forced farmers to sell their produce at whatever price the requisitioning officers chose to put on it. They were paid in quartermaster and commissary certificates, which also circulated as money at a fraction of their face value.

The need to deal effectively with the massive debts incurred in the Revolution was one of the main drivers of the Constitutional Convention that met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. The new Constitution and the monetary and tax systems put in place by Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, would keep inflation at bay until the great crisis of the Civil War came 75 years later.

Until the Civil War, paper money was printed by banks and it circulated at a value relative to the perceived soundness of the issuing bank. The United States minted copper and silver coins, but not high-value gold coins until after the California gold strike of 1848. In 1837, it set the price of dollars at $20.66 per troy ounce of gold, putting the country on the gold standard.

***

War is, by far, the most expensive of all government operations. And both the Confederate and United States governments faced unprecedented financial stresses in funding the Civil War. How each of them met the challenge helped determine, in no small degree, the outcome of the war.

Governments have only three ways to fund operations. They can tax, they can borrow, and they can print. Both governments did all three, but the particular mix was very different. The northern states had a much more advanced economy and a well-established financial system in place. As a result, the U.S. was able to throw much of the cost of the war onto the future. In 1860, the national debt had stood at $64 million. By 1866, it was at $2.7 billion, and about five percent of the North’s population had invested in federal bonds. So the North was able to raise two-thirds of its revenues by borrowing.

The Confederacy, with far less liquid capital, a much smaller middle class, and few large banks, could raise only about 40 percent of its revenues through bond sales.

The Confederacy, with far less liquid capital, a much smaller middle class, and few large banks, could raise only about 40 percent of its revenues through bond sales.

It was the same with taxes. The federal government sharply raised tariffs—its main source of income before the war—and excise taxes. It also taxed gross receipts and imposed a stamp tax on legal documents. The country’s first income tax was passed in 1862. Altogether the North raised 21 percent of its revenues through taxation. The Confederacy, with a less developed and cash-poor economy, was able to raise only about six percent of its revenues through taxation.

Thus the federal government needed to use the third means of raising revenue—printing fiat money—for only about twelve percent of its revenue needs. In the course of the war, the Treasury printed $450 million in “greenbacks” (so-called because they were printed in green on the reverse). This caused inflation, as fiat money always does, and prices rose over the course of the war in the North by a manageable 75 percent.

The South had to meet fully 50 percent of its revenue needs by printing money. State and city governments also printed money. And because the South lacked good paper mills and state-of-the-art printing facilities, counterfeiting flourished. Altogether, the South printed about $1.5 billion in fiat money, three times as much as the North, despite having only twelve percent of the circulating currency before the war and 21 percent of banking assets.

The result was catastrophic inflation. Prices rose 700 percent in the South in just the first two years of the war. As the war continued, the inflationary spiral deepened and the southern economy began to spin out of control. Living standards fell sharply while hoarding, shortages, and black markets spread, eroding popular support for the war.

With the end of the war, Confederate bonds and paper money became worthless—indeed, redemption of the bonds was explicitly forbidden by the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868. The South, deeply impoverished by the war and dependent on agriculture and extractive industries, would be essentially a third-world country inside a first-world country well into the twentieth century.

***

By 1879, greenbacks had been made redeemable in gold and the country had returned to the gold standard. The gold standard, where the government stands ready to buy or sell gold in unlimited quantities at a fixed price for its currency, makes inflation impossible. If the market begins to have doubts about the value of the currency, it will increasingly trade it for gold, as would foreign central banks. Consequently, the government must rein in the money supply to avoid being forced off the gold standard.

By 1879, greenbacks had been made redeemable in gold and the country had returned to the gold standard. The gold standard, where the government stands ready to buy or sell gold in unlimited quantities at a fixed price for its currency, makes inflation impossible. If the market begins to have doubts about the value of the currency, it will increasingly trade it for gold, as would foreign central banks. Consequently, the government must rein in the money supply to avoid being forced off the gold standard.

The gold standard was very popular with bankers and industrialists, as it protected the value of their assets. But it was equally unpopular with chronic debtors, such as farmers, who wanted to be able to pay back their loans with cheaper money.

Pulled in two directions, Congress—as legislatures in democratic countries often do—tried to have it both ways. It put the country fully back on the gold standard on January 1, 1879, soon after passing the Bland-Allison Act in 1878—an act requiring the Treasury to buy on the open market between $2 million and $4 million worth of silver every month and coin it at the ratio of 16-to-1 with gold.

That was roughly the free market price of silver at the time. But as silver production soared in the 1880s, thanks to such strikes as the Comstock Lode, the price of silver began to drop, reaching about 20-to-1 by 1890. That year, Congress passed the Sherman Silver Act, mandating that the Treasury buy and coin 4.5 million ounces of silver every month—just about all the silver the country was producing—still at the ratio of 16-to-1.

With the gold standard keeping the value of the dollar steady and the silver policy greatly increasing the money supply, the government managed both to forbid inflation and to guarantee it at the same time.

Inevitably, Gresham’s Law kicked in. With silver worth one-twentieth the price of gold in the marketplace, but one-sixteenth the price when coined as money, people increasingly kept the gold and spent the silver. Gold began to trickle out of the Treasury.

The very large budget surpluses of the 1880s masked the government’s schizophrenic monetary policy. But when the crash of 1893 marked the onset of a new depression and government revenues plunged, the trickle of gold out of the Treasury turned into a flood. Only some very fancy footwork by the country’s leading banker, J.P. Morgan, kept the U.S. from being forced off the gold standard in 1895.

The next year, William Jennings Bryan (D) ran for president on an expressly pro-inflation platform. In one of the most famous American political speeches ever given, he demanded that “you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” Bryan lost badly to William McKinley (R), who campaigned on a platform of sound money, and the country would stay on the gold standard until 1933.

***

The outbreak of World War I caused many disruptions in the American economy even before we entered the conflict two-and-a-half years later. With Russian grain exports blockaded, demand for American wheat soared, as did allied orders for ships, railroad rails, munitions, and other war matériel.

As a result, prices rose nearly 100 percent in the first two years of the war. When the United States entered the conflict, the federal government set up a series of boards to negotiate prices with producers to see that prices stayed in check while assuring a supply of vital materials. The Price Fixing Committee set maximum prices for such materials as coal and steel, but these maximum prices quickly became the standard prices. The only commodity that had a fixed price by statute was wheat.

With the end of the war 20 months later, the American economy soon returned to normal. Prices fell back to more modest levels, partly due to the very sharp, but short, recession of 1920-21.

The beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 brought not inflation but deflation, which can be an even bigger problem. When inflation is serious, people tend to spend money as soon as they get it, to avoid even higher prices in the future. But in a deflationary environment, people tend to postpone purchases in order to take advantage of lower prices in the future, further depressing the economy.

The Federal Reserve had pushed up interest rates in 1928 and 1929 in order to tamp down speculation on Wall Street. But after the crash of 1929, the Federal Reserve should have lowered them aggressively and—in the words of the late governor of the New York Federal Reserve, Benjamin Strong—“flood[ed] the street with money.”

Instead, it kept interest rates high. After Britain was forced off the gold standard in 1931, and the world economy spiraled downwards, the Federal Reserve still kept interest rates high to defend the gold standard in this country. As a result, the American money supply fell by a third in the early 1930s, greatly exacerbating the depression. To be sure, the huge number of bank failures in these years, more than 5,000, also contributed to deflation.

With the onset of World War II and the U.S. becoming the “arsenal of democracy,” inflation would have quickly returned as the American economy experienced shortages in many vital commodities. But strict wage and price controls were put in place and many commodities, such as sugar, butter, red meat, shoes, and gasoline, were severely rationed. Some commodities in particularly short supply, such as rubber and building materials, simply vanished from the marketplace.

But while the wage and price controls kept wartime inflation down to about 25 percent, they did not eliminate the inflationary pressures—they only postponed them. When President Truman ended wage and price controls at the beginning of 1946, inflation came roaring to life. The U.S. experienced the greatest peacetime inflation up to that point, as non-governmental spending rose by 40 percent. But the supply of goods could not expand nearly as quickly, as industry needed time to switch over to peacetime production.

In 1946, farm prices rose twelve percent in a single month and were 30 percent higher by the end of the year.

Many economists had thought that with the end of wartime government spending, the depression of the 1930s would return. It did not for several reasons. One was that during the war, with many products such as household appliances and automobiles unavailable, demand for these commodities built steadily. Further, with few things beyond necessities available in the marketplace, the savings rate was unprecedented. In 1940, Americans had held about $4.2 billion in savings, about the same as in 1929. In 1945, personal savings amounted to an astonishing $137.5 billion.

Wages, too, increased once controls were ended. As corporate profits in 1946 increased 20 percent, labor unions demanded higher wages and went on strike to get them. In January 1946, fully three percent of the workforce was on strike at the same time, including in the steel, automobile, electrical, and meatpacking industries.

By the late 1940s, with the government usually running modest budgetary surpluses and industry once again on a peacetime footing, inflation subsided and the economy grew quickly, doubling between the end of the war and the mid-1960s.

But it was not to last. When Lyndon Johnson acceded to the presidency on the death of John F. Kennedy, he wanted to complete the New Deal. He pushed through a number of programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, Head Start, and the Mass Transit Act. These new programs caused a breathtaking rise in non-defense federal expenditures. Between 1965 and 1968, they rose by a third, from $75 billion to $100 billion. Because of the Vietnam War, military expenses went up as well, from $50 billion to $82 billion.

This new spending inevitably caused an increase in inflation, which had been minimal since the immediate post-war years. A vicious cycle developed, with lenders demanding higher interest rates to protect them from inflation, while the Federal Reserve pumped up the money supply by buying federal bonds to keep interest rates down.

In 1974, Congress passed the Budget and Impoundment Control Act—as misnamed an act of Congress as it is possible for an act to be. It effectively removed the president as a player in the budget game, by ending his power to impound appropriated funds. With Congress in full control of spending, spending went out of control. In the six years preceding the Act, with the Vietnam War raging, annual deficits had averaged $11.3 billion. In the first six years after the Act, with the war over, they averaged $54 billion.

By 1980, the inflation rate hit 13.5 percent, the highest peacetime rate in history. Although the national debt increased by two-and-a-half times in the 1970s, so great was the inflation in that decade that the debt actually declined as a percentage of GDP.

Only when Paul Volcker became chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1979, and Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, did inflation end. The Federal Reserve sharply increased interest rates, pushing the economy into a deep recession. Unemployment hit 10.8 percent at its peak, the highest since the 1930s. But it worked. Inflation, which had been 13.5 percent in 1980, was down to 4.1 percent in 1984 and would stay low for the next few decades.

When the economy went into a deep recession with the bursting of the housing bubble in 2008, however, the government began running unprecedented budget deficits. The national debt, over $10 trillion in 2010, would double by 2017. With the onset of the COVID pandemic in 2020, deficits soared further as the government sought to mitigate the effects of shutting down much of the economy. The national debt now stands at $29 trillion—about where it was in 1945, relative to GDP.

But this breathtaking increase in the money supply did not, at least immediately, set off inflation. For while inflation is a monetary phenomenon, it is also a psychological one: when the expectation of inflation becomes widespread, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

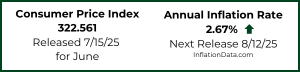

That prophecy was fulfilled in 2021. With the Biden administration continuing pandemic relief, which discouraged many from seeking work, and restricting oil and gas production, inflation set in. Supply chain disruptions also contributed.

By December 2021, consumer prices were up seven percent on an annual basis, the highest in 40 years, while producer prices were up 9.6 percent, the highest since that statistic has been compiled. And the expectation of further inflation is now deeply embedded in the economy.

Regardless of this, the Biden administration is still pushing hard for its “Build Back Better” plan, which would add at least another $5 trillion to the national debt over the next decade. And President Biden has airily said that “Milton Friedman is no longer in charge.”

But unfortunately for the Biden presidency—and for the U.S. economy and the American people—Milton Friedman was right. Create too much money and you get inflation. We are witnessing the proof of that right now.

About the Author: John Steele Gordon was educated at Millbrook School and Vanderbilt University. His articles have appeared in numerous publications, including Forbes, National Review, Commentary, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. He is a contributing editor at American Heritage, where he wrote the “Business of America” column for many years, and currently writes “The Long View” column for Barron’s. He is the author of several books, including Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt, The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power, and An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power.

About the Author: John Steele Gordon was educated at Millbrook School and Vanderbilt University. His articles have appeared in numerous publications, including Forbes, National Review, Commentary, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. He is a contributing editor at American Heritage, where he wrote the “Business of America” column for many years, and currently writes “The Long View” column for Barron’s. He is the author of several books, including Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt, The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power, and An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power.

Reprinted by Permission from Imprimis a publication of Hillsdale College

You might also like:

Leave a Reply