Having taken Thomas Piketty to the cleaners a few weeks back (see “Gave & Gave … and Hay”), Charles Gave now redresses the balance with regard to the issue of economic inequality in today’s Outside the Box. He makes a forceful case that “poverty matters for capitalists”:

Every US recession that I can recall was preceded by a fall in long rates, and I doubt the next will be much different. As such, do not expect the next US downturn to arise from the Federal Reserve pushing rates higher, an overvalued dollar or even mal-investments. Expect it to result from a decline in the income of the working poor. Early warning signs are likely to show up in the shopping aisles of stores such as Walmart, average driving miles, and the price of houses at the cheaper end of the market. I suspect the lesson that will eventually be learnt is that in a modern industrialized economy there are few worse things a central bank can do than deliberately attack the spending power of the poor.

Charles is clearly tying the economic struggle of the working poor to Federal Reserve policy. As he says, “negative real rates amounts to the Fed imposing a regressive tax on the poor although it lacks the authority to collect taxes.”

Income decline among the least wealthy in US society is not just an economic issue, he asserts:

At a moral level, I would also question the validity of a system that no longer allows its weakest members to get by. This is why I contend that the post-2010 policy of ZIRP has had little to do with protecting the health of the capitalist system, but rather has been a ruse to protect the rich. The policy is not only failing to deliver growth, it is also immoral.

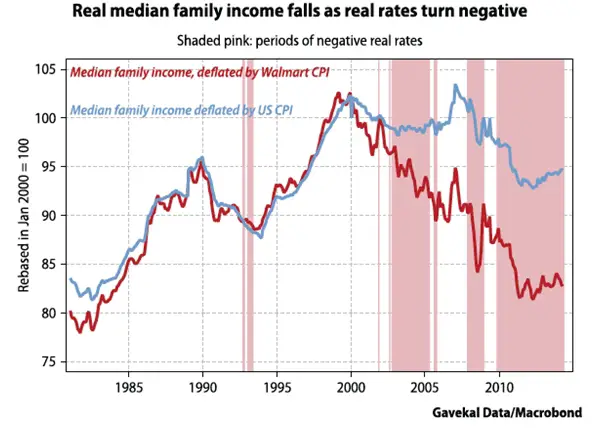

And that income decline has been drastic since 2000, and particularly since 2010. Charles has created what he calls a “Walmart CPI,” which tracks the prices of rent, food, and energy (the things the poor must spend nearly all their income on); and he uses it to demonstrate the effects of negative real rates on the poor. Since 2000 there has been more than a 15% increase in the ratio of the Walmart CPI to standard US CPI.

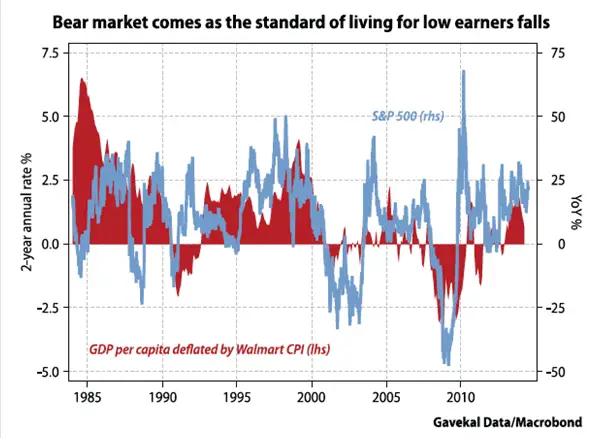

We can expect this deadly combination of rising prices for necessities and declining incomes to affect the stock market, too, says Charles:

Pretty much every equity bear market in the US over the last 30 years has occurred against the backdrop of the working poor experiencing a decline in living standards (the one exception was 1987 when the market was reacting to over valuation).

Strong stuff. But that’s Charles: never afraid to tell it like he sees it.

I am preparing to leave for Nantucket in a few hours, and I’m looking forward to the trip. I’ve never been there; and not only are my hosts providing very pleasant accommodations along the waterfront, they have also conveniently arranged for the weather to be nearly perfect. I have an iPad full of books that are all begging to be read, and of course a weekly letter will have to be teased out of my computer sometime in the next few days.

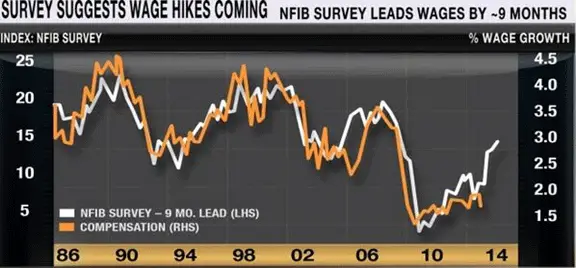

Wrapping up, two significant items hit my inbox this morning, including one from Andrew McCreath, who is a host for BNN in Canada. He uses data from my friend Bill Dunkelberg, Chief Economist of the National Federation of Independent Business (who will be visiting me in a few weeks here in Dallas), showing the correlation between certain aspects of the NFIB survey and wages. It will be good news for workers if wage hikes are in the offing, but that means that margins in businesses, which are sky-high right now, will come under pressure. This also plays well into Rosie’s (David Rosenberg’s) theme that we are going to see wage inflation soon, which he visualizes in interestingsa charts. Will this trend finally lead to some talk of interest rate increases? And yet I am told that Ben Bernanke, in his $250,000 speeches, is saying that we will not see much higher rates in his LIFETIME.

Maybe Ben (who is still young enough that “his lifetime” means a VERY long time) was reading David Kotok’s latest note this morning, as David worries a few trout in Wyoming:

Gasoline prices have reached levels that (1) will be sustained for a while in all likelihood and (2) that are, in real terms, equivalent to levels that previously led to economic slowdowns in the US. This development prompted our exit from [an overweight position in the Energy] sector.

In a compelling study, Ned Davis Research examined the real price of gasoline, adjusted for the inflation rate, and its economic impacts. The inflation-adjusted price of gasoline today has reached levels that have historically throttled growth. Furthermore, the Ned Davis study finds that a higher price for gasoline would be the equivalent of a major shock. The research suggests that under either circumstance – current gas prices or prices that surge even higher – the weight on the economy from that adjustment is onerous.

And I just can’t close without this brief, ironic comment. Readers may know that I have neighbors who question my Texas ancestry (which goes back to the Republic, thank you) because I don’t own any guns. I am perfectly content for my friends to have lots of them and feel gun ownership is one of those sacred rights, but I have just never been motivated to build a bunker with an arms locker, or even possess a small pistol. For whatever reason, I feel perfectly safe without one.

With that admission (which some will applaud and others see as a glaring lapse of character), I note that over the 4th of July weekend, there were 82 people shot, 14 fatally, in Chicago.

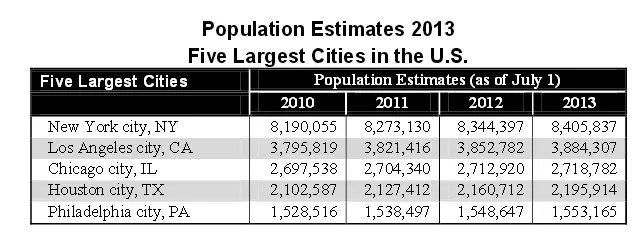

I read elsewhere that Houston had six shot and two dead over that same period. Chicago, the third-largest city in the US, has no places where you can legally buy a gun. Houston, the fourth-largest US city, has over 500 (including Walmarts, etc., which are not listed as gun stores per se but have rather extensive offerings). Not sure what that means, but you have to wonder.

Editor’s note:

John’s comment got me to thinking about the comparative populations of Houston vs. Chicago maybe Chicago is a lot bigger… and so after a bit of Googling I found that Chicago has a population of 2,718,782 ( roughly 2.72 million) while Houston is not that far behind at 2,195,914 (2.2 million) so over the weekend in question Houston had 1 killing per every 1.1 million people with 500 gun outlets and Chicago had 1 killing for every 194,199 people with no gun stores… roughly 5.7 times greater… hmm. Also according to the 2000 Census Chicago’s population was larger at 2,896,016 and Houston was 1,953,631. So Chicago is actually declining in size while Houston is the fastest growing. Soon Houston may be the 3rd largest city in the country. See the Article below for Gave’s full commentary on Capitalism. ~ Tim McMahon, editor.

Have a great week. And enjoy your summer! I know most farmers are, as the weather is perfect for growing all sorts of crops, which look to produce record yields in the US this year.

Your going to be reading about GDP this week analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Boxsubscribers@mauldineconomics.com

Stay Ahead of the Latest Tech News and Investing Trends…

Click here to sign up for Patrick Cox’s free daily tech news digest.

Each day, you get the three tech news stories with the biggest potential impact.

Poverty Matters for Capitalists

By Charles Gave

GaveKal Dragonomics

July 8, 2014

Inflation is a much misunderstood phenomenon. Most people assume that a CPI rate of 10% means that most prices are rising by a similar amount. In reality, some prices may be falling even while others soar. This matters because price variations affect socio-economic groups in very different ways. The rich tend not to be impacted unduly by price hikes for “necessities” such as food, rent and fuel, while the impact on the poor is to slash that portion of their income left over for discretionary spending.

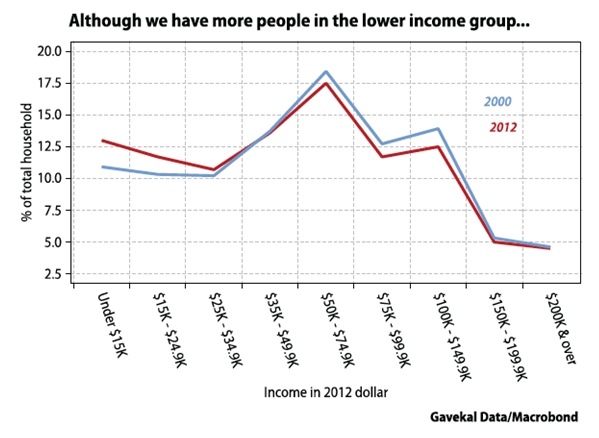

A sharp rise in the price of staples imposes an effective tax on low earners, resulting in recession conditions for firms that sell to them. The broad picture in the US may be of low interest rates and rising real average incomes, but the poor have seen their real incomes slashed since 2008 and with scant subsequent improvement. The poor also own few assets. Aside from the inequity of such a situation, the macro concern is that the erosion of real incomes creeps up the earning scale so that middle earners eventually see an erosion of living standards. At some point, the decline in activity created by a fall in average incomes will lead to a recession.

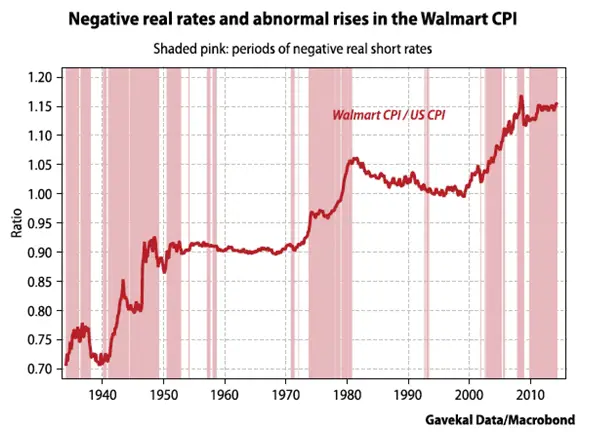

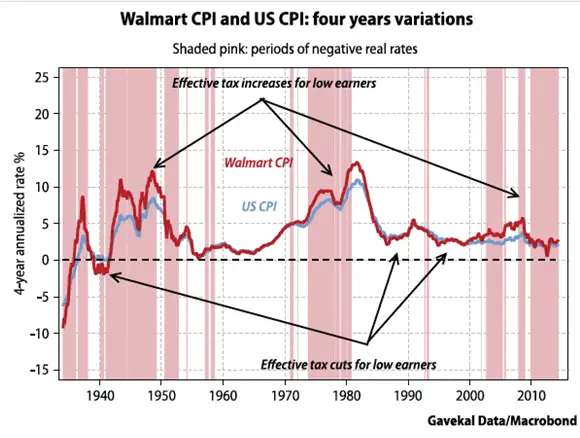

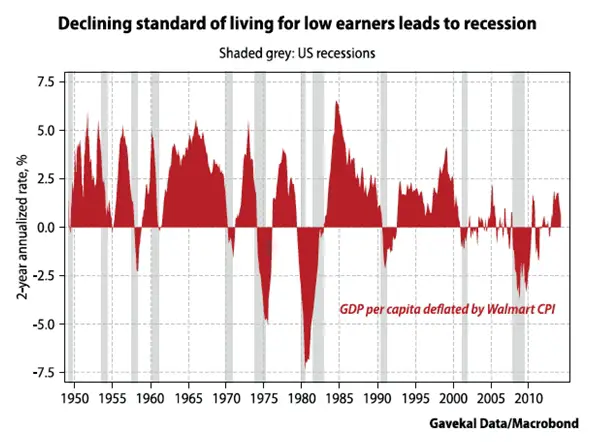

I have tested this postulate by building a US inflation index comprised of price variations for oil, food and rent. This can be seen in the chart below where rent is weighted at 50%, food at 30% and energy at 20%. I term this price measure the Walmart Index since it is where most low earners tend to shop. The chart shows the relationship since 1934 between the US CPI and my adapted measure of the price index most relevant to the lives of the least well-off in America.

There is a clear relationship between periods of rising prices for essential items and negative real rates. Such a policy undermines the dollar as a store of value. As a result, investors seek alternatives such as gold, oil and agricultural land (see The High Cost Of Free Money). Boiled down, the impact for low earners is an abnormal rise of the Walmart CPI vs the US CPI. Put another way, negative real rates amounts to the Fed imposing a regressive tax on the poor although it lacks the authority to collect taxes.

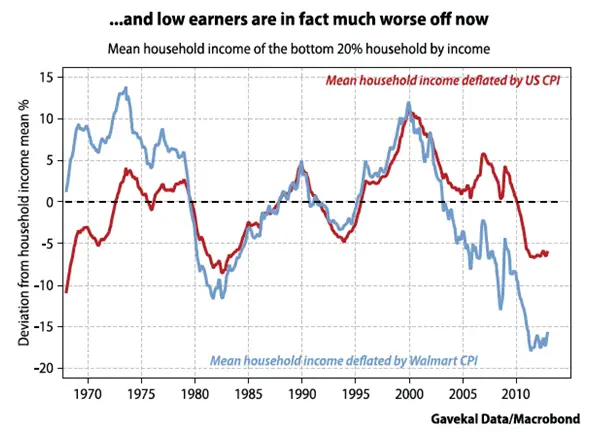

The chart below shows the impact of this effective tax hike on household incomes. The actual income of the low income group varies more when measured against the price of necessities rather than the broad CPI.

Looking back, it is clear that America’s working poor did pretty well between 1982 and 2000, and had a bad time in the ensuing period, when real interest rates have, for the most part, been negative.

Looking back, it is clear that America’s working poor did pretty well between 1982 and 2000, and had a bad time in the ensuing period, when real interest rates have, for the most part, been negative.

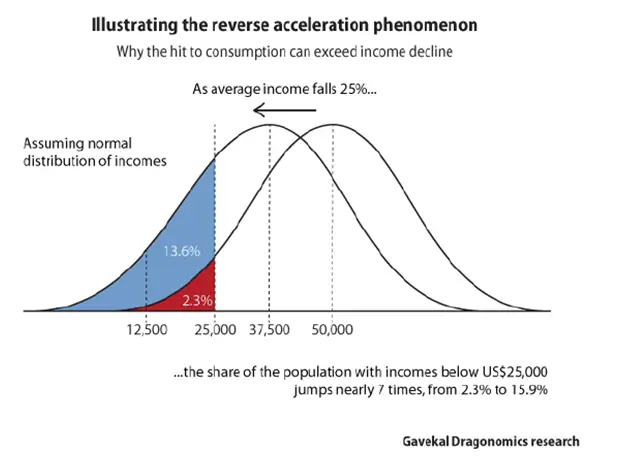

Next, consider the “acceleration phenomenon”, which we have often used to explain the non-linear dynamics of consumption. We have mostly used this tool to show spending in developing economies experiencing real income growth. Sadly, we now apply the method to the US under reversed conditions. The framework begins with the observation that the propensity to spend on certain goods does not rise smoothly with income, but moves in steps: households just above a certain income threshold are much more likely to buy say, a car, than households just below it; hence the notion of “acceleration”. Our thesis is that significant sections of the US population have stopped consuming certain bigger ticket items. For illustration, the chart below shows the likely impact of a 25% fall in average incomes.

The economic impact

The chart below shows a worrying relationship between the standard of living, as measured by the Walmart CPI, and US recessions.

Going back to 1970 each time the lower income group of Americans experienced a fall in their standard of living for two years or more, the period ended with a recession. This is the inevitable arithmetical outcome from pursuing policies which crimp the incomes of that population cohort most inclined to spend what they earn. At a moral level, I would also question the validity of a system that no longer allows its weakest members to get by. This is why I contend that the post-2010 policy of ZIRP has had little to do with protecting the health of the capitalist system, but rather has been a ruse to protect the rich. The policy is not only failing to deliver growth, it is also immoral.

The stock market impact

Pretty much every equity bear market in the US over the last 30 years has occurred against the backdrop of the working poor experiencing a decline in living standards (the one exception was 1987 when the market was reacting to over valuation).

Conclusion

Every US recession that I can recall was preceded by a fall in long rates and I doubt the next will be much different. As such, do not expect the next US downturn to arise from the Federal Reserve pushing rates higher, an overvalued dollar or even mal-investments. Expect it to result from a decline in the income of the working poor. Early warning signs are likely to show up in the shopping isles of stores such as Walmart, average driving miles, and the price of houses at the cheaper end of the market. I suspect the lesson that will eventually be learnt is that in a modern industrialized economy there are few worse things a central bank can do than deliberately attack the spending power of the poor.

Given the Fed’s asinine policy stance, at least since 2002, it seems likely that the prices of discretionary items bought by the least well off are likely to slip into a protracted decline. Hence, the deflationary tendencies that have been visible for some years are likely to explode during the process of a deflationary contraction. The fact that the price of oil, gas and rents has continued to rise only hardens my conviction in this view.

I make no claim on the timing of this outcome. But the end game for this cycle is surely for US long rates to decline and quality spreads to open massively. My advice would be to maintain a deflation hedge in all portfolios, improve liquidity and boost the quality of both bond and equity holdings.

Like Outside the Box?

Sign up today and get each new issue delivered free to your inbox.

It’s your opportunity to get the news John Mauldin thinks matters most to your finances.

About John Mauldin

Each week, well over a million readers turn to John Mauldin to better understand Wall Street, global markets, and the drivers of the world economy. And for good reason. John is a renowned financial expert, a New York Times best-selling author, a pioneering online commentator, and the publisher one of the first publications to provide investors with free, unbiased information and guidance, Thoughts from the Frontline—the most widely read investment newsletter in the world. More...

- Web |

- More Posts(10)

Leave a Reply