By Ben Hunt, Ph.D.

Previously, we discussed the Bureaucratic Capture of the FED and the institutionalizing of QE.

QE is adrenaline delivered via IV drip … a therapeutic, constant effort to maintain a certain quality of economic life. This may or may not be a positive development for Wall Street, depending on where you sit. I would argue that it’s a negative development for most individual and institutional investors. But it is music to the ears of every institutional political interest in Washington, regardless of party, and that’s what ultimately grants QE bureaucratic immortality.

It is impossible to overestimate the political inertia that exists within and around these massive Federal insurance programs, just as it is impossible to overestimate the electoral popularity (or market popularity, in the case of QE) of these programs. In the absence of a self-imposed wind-down plan – and that’s exactly what Bernanke laid out in June and exactly what he took back on Wednesday – there is no chance of any other governmental entity unwinding QE, even if they wanted to.

The long-term consequences of this structural change in the Fed are immense and deserve many future Epsilon Theory notes. But in the short to medium-term it’s the procedural shifts that have been signaled this week that will impact markets. What does it mean for market behavior that Bernanke intentionally delivered an informational shock by forcing uncertainty into market expectations?

The long-term consequences of this structural change in the Fed are immense and deserve many future Epsilon Theory notes. But in the short to medium-term it’s the procedural shifts that have been signaled this week that will impact markets. What does it mean for market behavior that Bernanke intentionally delivered an informational shock by forcing uncertainty into market expectations?

First, it’s important to note that this is not really an issue of credibility. The problem is not that people don’t believe that Bernanke means what he said on Wednesday, or that they won’t believe him if he says something different in October. The problem is that the Fed is entirely believable, but that the message is not one of “constructive ambiguity” as the academic papers written by Fed advisors intend, but one of vacillation and weakness of will.

From a game theory perspective, ambiguity can be a very effective strategy in pretty much whatever game you are playing. Alan Greenspan was a master of this approach, famous for the lack of clarity in his public statements. Other well-known practitioners of intentionally opaque statements include Mao Zedong (hilariously lampooned in Doonesbury when Uncle Duke had a short-lived stint as the US Ambassador to China) as well as most Kremlin communications in the Soviet era. Clarity and transparency can also be a very effective strategy in pretty much any game, particularly if you’re playing a strong hand or you want to make sure that your partner follows your lead. For example, throughout the Cold War both the Americans and the Russians would place certain strategic assets in plain sight of the other country’s surveillance apparatus so that there would be no mistaking the strength and intent of the signal.

The key to the success of both strategies – intentional ambiguity and intentional clarity – is consistency and, very rarely, the “gotcha” moment of a strategy switch. To use a poker analogy, the tight player who has a reputation for never bluffing can take down a big pot with a bluff much more easily than a player who is impossible to read and has a reputation as a frequent bluffer. Of course, this bluff can only be used once in a blue moon or the reputation for being a tight player will be lost, as will future bluffing effectiveness. Also, the reputation as a tight player must be established effectively prior to the first bluff.

To stick with the poker analogy, here’s my take on what the Fed has done. For the past four months, they’ve tried to create a reputation as a tight player, meaning that they have laid out fairly clear standards for how they will interpret labor data (the equivalent of cards dealt face up) to set the extent and timing of QE tapering. The market responded as it always does, setting its expectations on the basis of the Fed’s statements, and moving up or down as each new labor data card was revealed. But then on Wednesday, the Fed revealed a bluff to win … nothing … and announced that they would now be playing in an unpredictable fashion. It was almost as if Bernanke had read a beginner’s poker instruction book when he was at Jackson Hole in late August that said you have to be a hard-to-read player who bluffs a lot to succeed at poker, and decided as a result to change his entire strategy. I don’t know what you would think about a player like that in your poker game, but words like “weak”, “fish”, and “donkey” come to my mind.

In fact, I think that the poker instruction book metaphor is just barely a metaphor, because we know that several papers at Jackson Hole took Bernanke to task for his communication policy to date. For example, Jean-Pierre Landau, a former Deputy Governor of the Bank of France and currently in residence at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School, presented a paper focused on the systemic risks of the massive liquidity sloshing around courtesy of the world’s central banks. For the most part it’s a typical academic paper in the European mold, finding a solution to systemic risks in even greater supra-national government controls over capital flows, leverage, and risk taking. But here’s the interesting point:

“Zero interest rates make risk taking cheap; forward guidance makes it free, by eliminating all roll-over risk on short term funding positions. … Forward guidance brings the cost of leverage to zero, and creates strong incentives to increase and overextend exposures. This makes financial intermediaries very sensitive to “news”, whatever they are.”

Landau is saying that the very act of forward guidance, while well-intentioned, is counter-productive if your goal is long-term systemic stability. There is an inevitable shock when that forward guidance shifts, and that shock is magnified because you’ve trained the market to rely so heavily on forward guidance, both in its risk-taking behavior (more leverage) and its reaction behavior (more sensitivity to “news”). This argument was picked up by the WSJ (“Did Fed’s Forward Guidance Backfire?”), and it continued to get a lot of play in early September, both within the financial press and from FOMC members such as Narayana Kocherlakota.

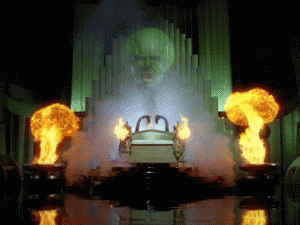

I think that Bernanke took these papers and comments to heart … after all, they come from fellow trusted members of the academic club … and decided to change course with communication policy. No more clearly stated forward guidance, but rather the oh-so-carefully crafted ambiguity of an Alan Greenspan. Here would be a Monster that can sing and dance, one that can be trotted on stage in a tux and tails and is sure to delight the audience with a little number by Irving Berlin. What could possibly go wrong? Well, the same thing as the first performance back in June – a complete misunderstanding of the real-world environment into which these signals are injected.

At least in June the Fed still projected an aura of resolve. Today even that seems missing, and that’s a very troubling development. Creating a stable Narrative is a function of inserting the right public statement signals into the Common Knowledge game. As described above, it really doesn’t matter what the Party line is, so long as it is delivered with confidence, consistency, and from on high. But once the audience starts questioning the magician’s sleight-of-hand mechanics, once the Great and Terrible Wizard of Oz is forced to say “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain”, the magician has an audience perception problem. Fair or not, there is now a question of competence around Fed policy and its decision-making process. Sure the Monster can sing, but can it sing well?

Unfortunately, I think that this perception of an irresolute, somewhat confused Fed is poised to accelerate in the forthcoming nomination proceedings for a new Chair, not dissipate. If strength of will and resolve of purpose is the quality you need to project, then the Fed needs a Strongman on a Horse:

not a Wise Oracle Baking Cookies.

Sorry, but it’s true.

I mean, does anyone doubt that Janet Yellen is a consensus builder who would feel more at home at a faculty tea with Elizabeth Warren than a come-to-Jesus talk with Zhou Xiaochuan? Does anyone doubt that Larry Summers is the polar opposite, a bureaucratic Napoleon who would absolutely revel in lowering the boom on Zhou or Tombini … or Bullard or Yellen, for that matter? But it looks like Yellen is the shoo- in candidate, so whatever perceptions of Fed wishy-washiness and indecision that are currently incubating are likely to grow, no matter how unfair those perceptions might be.

What does all this mean for how to invest in the short to medium-term? Frankly, I don’t think that “investment” is possible over the next few months, at least not as the term is usually understood, and at least not in public markets. When you listen to institutional investors and the bulge-bracket sell-side firms that serve them, everything today is couched in terms of “positioning”, not “investment”, and as a result that’s the Common Knowledge environment we all must suffer through. This is the fundamental behavioral shift in markets created by a Fed-centric universe – the best one can hope for is a modicum of protection from the caprice of the Mad God, and efforts to find some investable theme are dashed more often than they are rewarded. The Narrative of Central Bank Omnipotence – that all market outcomes are determined by monetary policy, especially Fed policy – is stronger than ever today, so if you’re looking to take an exposure based on the idiosyncratic attributes or fundamentals of a publicly traded company … well, I hope you have a long time horizon and very little sensitivity to the price path in the meantime. I will say, though, that the counter-narrative of the Fed as Incompetent Magician, which is clearly growing in strength right alongside the Omnipotence Narrative, makes gold a much more attractive option than this time a year ago.

As for where all this game-playing and stage-strutting ultimately ends up, I want to close with two quotes by academics who are very far removed from the self-consciously (and self-parodying) “scientific” world view of modern economists. Weaver and Midgley are from opposite ends of the political spectrum, but they come to very similar conclusions. I’ll be examining the paths in which the “birds come home to roost”, to use Arthur Miller’s phrase, in future notes. I hope you will join me in that examination, and if you’d like to be on the direct distribution list for these free weekly notes please sign up at Follow Epsilon Theory.

The scientists have given [modern man] the impression that there is nothing he cannot know, and false propagandists have told him that there is nothing he cannot have. – Richard M. Weaver, “Ideas Have Consequences”

Hubris calls for nemesis, and in one form or another it’s going to get it, not as a punishment from outside but as the completion of a pattern already started. – Mary Midgley, “The Myths We Live By”

See: Taper Caper: Conspiracy Theory (intro) and Taper Caper: Has the FED Been “Politicized” or “Captured”?

Like Outside the Box? Sign up today and get each new issue delivered free to your inbox. It’s your opportunity to get the news John Mauldin thinks matters most to your finances.

© 2013 Mauldin Economics. All Rights Reserved. Outside the Box is a free weekly economic e-letter by best-selling author and renowned financial expert, John Mauldin. You can learn more and get your free subscription by visiting www.MauldinEconomics.com.

Leave a Reply