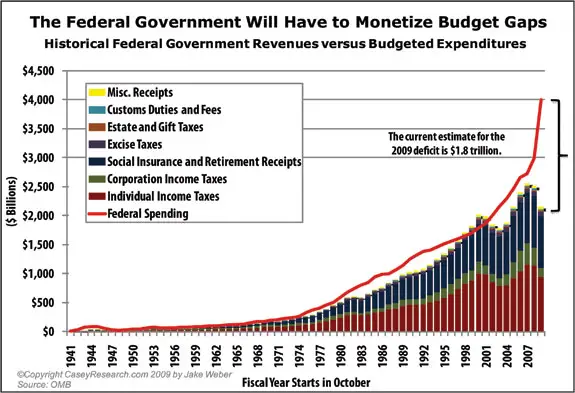

Case in point, in January the government projected a $1.2 trillion deficit for fiscal year 2009… in March, just three months later, they upped the projection to $1.8 trillion. That $600 billion “adjustment” alone totaled more than any full-year budget deficit in the nation’s history.

Yet, the real fly in the ointment is that the actual borrowing by the Treasury is likely to be at least half a trillion dollars more than the deficit.

That’s because the Treasury is buying toxic paper (mortgage, credit card loans, etc.) and putting them on the books with a higher value than the market is willing to assign. While that makes the budget deficit appear smaller, it doesn’t negate the fact that the government still must borrow the money needed to buy the toxic paper in the first place. The additional revenue shortfall means they have to raise that much more money. Based on the struggle they had pushing the $14 billion in long-term notes at the latest auction, it becomes increasingly apparent that when push comes to shove, the only way the government is going to come up with the money needed to meet its aggressive spending is to print it up.

In other words, events are rolling out almost exactly as we have been anticipating. Below, for example, are some useful excerpts from an April 3 article titled “Widening Deficits” by Casey Research CEO Olivier Garret. To quote…

In the midst of the Great Depression, the 1931 federal tax revenues had fallen by 52% from their 1929 highs. While we do not expect anything that dramatic in 2009, it would not be unrealistic to see a 20% to 25% reduction in cash flow from tax collections this tax season. Such a drop would pose significant challenges given that spending commitments are off the charts and climbing.

Later in that same article, Olivier continued,

In the absence of sizeable increases in tax revenues, it is quite clear that the lion’s share of the planned sales of Treasuries in 2009 cannot be met by demand from the market. Either the Treasury will have to raise interest rates significantly, or the Fed will need to step in very aggressively to support the planned auctions. Our expectation is that both will happen. Auctions will fail and the Fed will step in. The market will react to more printing by anticipating inflation and demanding higher interest rates. Once the cycle starts, it will be very hard to pull interest rates back.

We continue to stand by our December forecast that the 2009 budget deficit is more likely to widen to levels between $2.5 and $3 trillion rather than the CBO’s $1.8 trillion forecast. We also believe that inflation could start setting in as early as Q3 of 2009 and will accelerate sharply by 2010. Treasury Rates will start climbing and the era of cheap money will end, making it harder for overleveraged consumers, businesses, and governments to service their debt.

Olivier’s forecast of failed auctions and rising interest rates on Treasuries proved more prophetic as a May 7th story from Bloomberg reported:

Treasury 30-year bonds fell the most in four months as investors demanded higher-than-forecasted yields at today’s auction of $14 billion of the securities with the U.S. slated to sell a record amount of debt this year.

“This is a problem,” said Chris Ahrens, head interest-rate strategist at UBS AG in Stamford, Connecticut, one of 16 primary dealers required to bid in Treasury auctions. “The market required a fairly significant discount to buy the bonds.”

Thirty-year bonds have lost investors 20.9 percent this year, Merrill Lynch & Co. indexes show, as the Treasury increases securities sales to help fund a swelling budget deficit. Yields climbed to a six-month high today as the auction drew a yield of 4.288 percent, higher than the 4.192 percent average forecast in a Bloomberg News survey of seven primary dealers. Demand was below average, judging by total bids.

The benchmark 30-year bond yield climbed 23 basis points, or 0.23 percentage points, the most since Jan. 5, to 4.316 percent, at 5:25 p.m. in New York, according to BGCantor Market data. It was the highest yield since Nov. 14. The 3.5 percent security due in February 2039 dropped 3 15/32, or $34.69 per $1,000 face amount, to 86 3/8.

The 10-year note yield increased 16 basis points to 3.345 percent, the highest since Nov. 24.

Two-year notes yielded 1 percent for the first time since March 18, while the rate on the three-month Treasury bill was 0.18 percent.

So, what does all this mean?

The rock-and-the-hard-place scenario we have been predicting is unfolding before our eyes. At this point, other than sharply changing course and letting the free market cope with the crisis through a brutal “survival of the fittest” scenario, the government is left with no other option than to accelerate its buying up of its own debt.

Which is to say, it must push even harder on the levers of its printing presses, further setting the stage for the massive period of inflation we continue to see as inevitable… and for the stunning rise in interest rates we are now positioning ourselves for in The Casey Report .

Leave a Reply