What Is Price Stickiness?

Price stickiness, aka. “Sticky prices” are prices that tend not to change very quickly. So, despite costs (or demand) going up, a business with “sticky prices” may not raise its prices for an extended period of time. In other words, sticky prices tend to change slowly despite changing underlying factors. Sticky prices are a key component of Macroeconomic theory.

Why wouldn’t a business raise prices if its costs are going up?

You would think that most products and services would respond to the laws of supply and demand, i.e., when demand goes up, prices quickly follow. Or, when underlying costs rise a business would automatically raise its own prices to maintain profitability. However, with certain goods and services, this does not always happen immediately.

The reason a business wouldn’t raise prices quickly is that they have certain costs associated with raising prices. These costs are called “menu costs”. The term originates from the cost of restaurants literally having to print new menus. Businesses with high ‘menu costs’ tend to have sticky prices.

Other examples of “menu costs” include changing advertising that mentions a price, printing new brochures, etc.

Another factor contributing to price stickiness can be imperfect information in the markets or irrational decision-making by company executives. For instance, some companies may try to keep prices constant as a business strategy, even though it isn’t sustainable on a long-term basis. Other factors in stickiness could be long-term contracts where a purchaser has locked in prices for the longer term.

Some prices are more “sticky” than others.

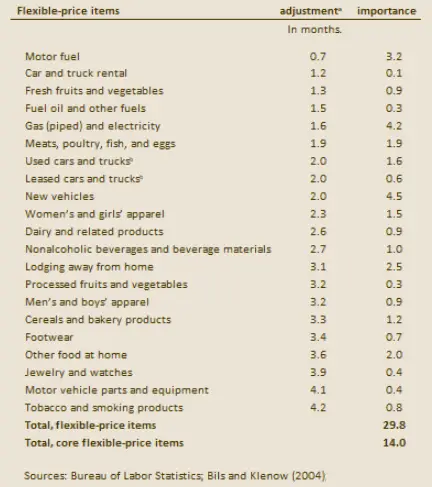

Back in 2010, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland published a chart of the relative stickiness of different categories of prices, with motor fuel the least sticky, i.e., they change the quickest at 0.7 months. In other words, it takes about 3 weeks for gas stations to change their prices based on underlying costs. Slightly more sticky are car rental costs, and fresh fruit and vegetable costs. These are called “flexible prices”.

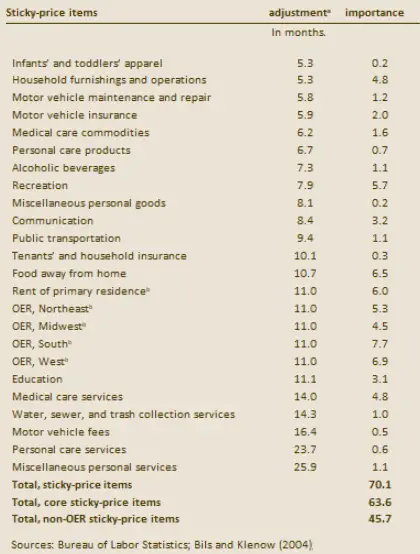

At the other end of the spectrum (i.e., the stickiest prices), are Education costs which take around 11 months to change, Medical Care costs, which take 14 months to change, and Personal Care Services which take about 2 years to change.

Flexible and Sticky Prices in the CPI Market Basket

The following chart shows the most flexible prices in months and their relative importance in the CPI basket.

Sticky Prices Example

This chart shows the stickiest prices in months and their relative importance in the CPI basket.

The Stickiest Price Ever

The early days of Coca Cola provide an example of the stickiest price. From its invention in 1886 to the late 1950s, the price of a bottle of Coke held at a nickel — even as most other product’s prices rose dramatically through 70 years of inflation.

The main reason? Vending machines.

Most vending machines that sold Coca Cola only took nickels, and if the company wanted to overhaul those machines to take dimes, they’d have to double the price of their product.

Fearing customer frustration and the loss of business that would come with it, Coke opted to keep charging five cents for their product for the better part of a century.

Stickiness in Just One Direction

In some circumstances, prices can be sticky in just one direction. People tend to believe that “prices go up but never go down”, which may have some basis in reality. This is partially because once people get used to paying a higher price they are less likely to object to paying that price, so without some compelling reason (like added competition), sellers find no reason to lower their prices even if their cost decreases. This is called being “sticky-down”.

The opposite would be “sticky-up” if it can move down rather easily but will only move up with pronounced effort.

Wage Stickiness

The idea of price stickiness can also be applied to wages or salaries. As workers become accustomed to earning a certain wage, they are highly resistant to taking a pay cut, and so wages tend to be sticky. In his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, John Maynard Keynes argued that nominal wages display downward stickiness, because workers are reluctant to accept cuts in nominal wages.

Leave a Reply